Yes, We Still Make Stuff, and It Wouldn’t Matter if We Didn’t – Article by Steven Horwitz

One of the perennial complaints about the US economy is that we don’t “make stuff” anymore. You hear this from candidates from both major parties, but especially from Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. The argument seems to be that our manufacturing sector has collapsed and that all US workers do is to provide services, rather than manufacturing tangible goods.

It turns out that this perception is wrong, as the US manufacturing sector continues to grow and in 2014 manufacturing output was higher than at any point in US history. But even if the perception were correct, it does not matter. The measure of an economy’s health isn’t the quantity of physical stuff it produces, but rather the value that it produces. And value comes in a variety of forms.

Manufacturing is Up

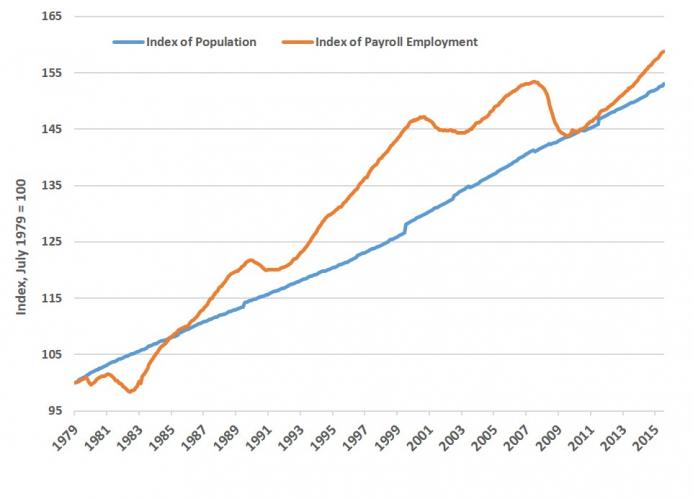

The path to economic growth is not to freeze into place the US economy of the 1950s. Let’s deal with the myth of manufacturing decline first. The one piece of evidence in favor of that perception is that there are fewer manufacturing jobs today than in the past. Total manufacturing employment peaked at around 19 million jobs in the late 1970s. Today, there are about 12.5 million manufacturing jobs in the US.

However, manufacturing output has never been higher. The real value of US manufacturing output in 2014 was over $2 trillion. The real story of the US manufacturing sector is that we have become so much more efficient, that we can produce more and more manufactured goods with less and less labor. These efficiency gains are largely the result of computer technology and automation, especially in the last fifteen years.

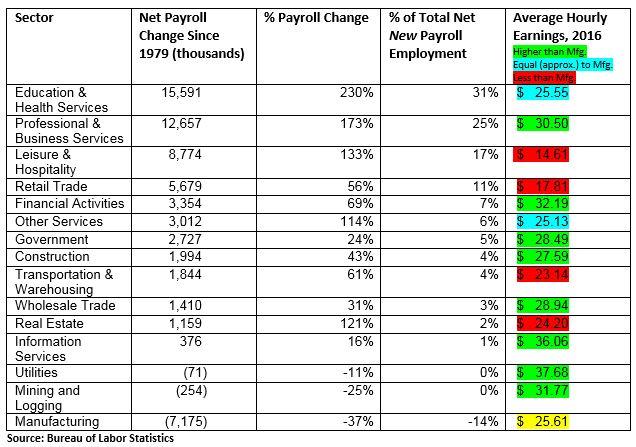

The labor that we no longer need in order to produce an ever-increasing amount of stuff is now available to produce a whole variety of other things we value, from phone apps to entertainment to the expanded number and variety of grocery stores and restaurants, to the data analyses that makes all of this growth possible.

Just as the workers in those factories we are so nostalgic for were labor freed from growing food thanks to the growth in agricultural productivity, so are today’s web designers, chefs at the newest hipster café, and digital editors in Hollywood the labor that has been freed from producing “stuff” thanks to greater technological productivity.

Or, put differently: those agricultural, industrial, and computer revolutions collectively have enabled us to have more food, more stuff, and more entertainment, apps, services, and cage-free chicken salads served with kale. The list of human wants is endless, and the less labor we use to satisfy some of them, the more we have to start working on other ones.

But notice something: all of the things that we produce have something in common. Whether it’s food or footwear, or automobiles or apps, or manicures or massages, the point of production is to rearrange capital and labor in ways that better satisfy wants. In the language of economics, the point of production (and exchange) is to increase utility.

When we produce more cars that people wish to buy, it increases utility. When we open a new Asian fusion street food taco stand, it increases utility. When Uber more effectively uses the existing stock of cars, it increases utility. When we exchange dollars for manicures, it increases utility.

Adam Smith helped us to understand that the wealth of nations is not measured by how much gold a country possesses. Modern economics helps us understand that such wealth is not measured by how much physical stuff we manufacture. Increases in wealth happen because we arrange the physical world in ways that people value more.

Neither producing cars nor providing manicures changes the number of atoms in the universe. Both activities just rearrange existing matter in ways that people value more. That is what economic growth is about.

Misplaced Nostalgia

We’re richer because we have allowed markets to produce with fewer workers. When we are fooled into believing that “growth” is synonymous with “stuff,” we are likely to make two serious errors. First, we ignore the fact that the production of services is value-creating and therefore adds to wealth.

Second, we can easily believe that we need to “protect” manufacturing jobs. We don’t. And if we try to do so, we will not only stifle economic growth and thereby impoverish the citizenry, we will be engaging in precisely the sort of special-interest politics that those who buy the myth of manufacturing often rightly complain about in other sectors.

The path to economic growth is not to freeze into place the US economy of the 1950s. We are far richer today than we were back then, and that’s due to the remaining dynamism of an economy that can still shed jobs it no longer needs and create new ones to meet the ever-changing wants of the consumer.

The US still makes plenty of stuff, but we’re richer precisely because we have allowed markets to do so with fewer workers, freeing those people to provide us a whole cornucopia of new things to improve our lives in endless ways. We can only hope that the forces of misplaced nostalgia do not win out over the forces of progress.

Steven Horwitz

Steven Horwitz is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Economics at St. Lawrence University and the author of Hayek’s Modern Family: Classical Liberalism and the Evolution of Social Institutions.

He is a member of the FEE Faculty Network.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.