Globalization’s So-Called Winners and Losers – Article by Chelsea Follett

A recent Washington Post analysis has argued that political events as diverse as the Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump can be explained by a “revolt” of the world’s economic “losers.”

Before proceeding, it is important to keep in mind that all income groups in the world have seen gains in real income over the last few decades. That said, some have gained more than others. Between 1988 and 2008, for example, the lowest gains were made by people whose incomes fit beteen the world’s 75th to 90th income percentiles. That includes much of the middle and working class in rich countries.

The Washington Post calls the people in this group the bitter “losers” of globalization. But, are they?

There are at least two problems with characterizing such people as “losers.” First, it seems to suggest that income growth rate matters more than absolute income level. Yet a person in the 80th income percentile globally would not want to trade places with or envy someone in the bottom 10th percentile, despite the latter’s much higher income growth rate.

There are at least two problems with characterizing such people as “losers.” First, it seems to suggest that income growth rate matters more than absolute income level. Yet a person in the 80th income percentile globally would not want to trade places with or envy someone in the bottom 10th percentile, despite the latter’s much higher income growth rate.

Consider real GDP per person, adjusted for differences in purchasing power, in China and the United States. Between 1988 and 2008, China’s per person GDP grew by over 340 percent. America’s per person GDP, in contrast, grew by “only” 40 percent. China may be making gains more quickly, but it would be wrong to argue that the United States was a “loser,” for American GDP per person in 2008 was $52,704 and China’s $8,104.

Poor countries are seeing faster income gains partially because their starting point is so much lower—it’s a lot easier to double per person GDP from $1,000 to $2,000 than from $40,000 to $80,000.

The second problem is that the Washington Post piece suggests that the incredible escape from poverty that has occurred in poor countries during my lifetime has come at the expense of the middle classes in the developed world. (This is a fascinating reversal of the more popular, but equally inaccurate, opinion that the Western riches came at the expense of poor countries).

Thus, the Washington Post piece claims, “global capitalism didn’t always work so well for workers in the United States and Europe even as—or, in some cases, because [emphasis mine]—it pulled hundreds of millions of people out of poverty everywhere else.”

Fortunately, prosperity is not a zero sum game.

When trying to understand the “winners” and “losers” of globalization, it is important that we do not compare income growth rates over the last few decades with some imagined ideal. Instead, we should compare income growth to what would have happened in a world without globalized trade. In such a world, hundreds of millions of people would have remained in extreme poverty. And the middle class of the developed world would also have made fewer gains. Just look at the amazing reduction in price of consumer goods that we have collected at HumanProgress.

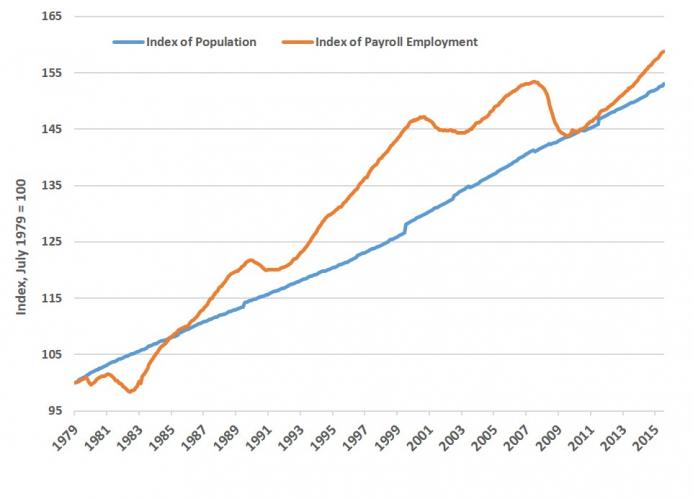

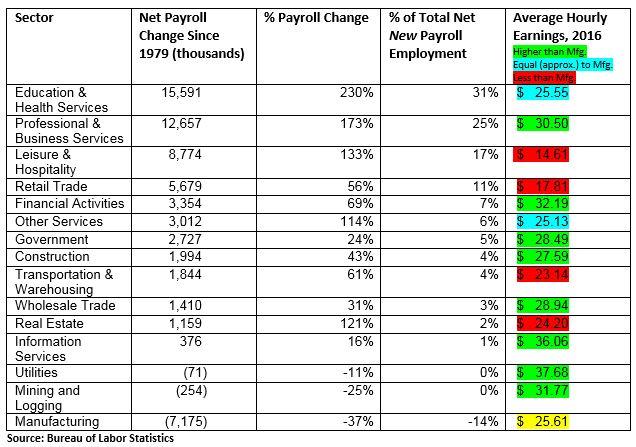

A few individuals in select industries would benefit from protectionism, like the U.S. sugar industry does now. But on average everyone would be poorer, just as in 2013 Americans collectively paid 1.4 billion dollars more for sugar than they would have without protectionism. (The U.S. manufacturing industry, it may be worth noting, would not be among the “select industries” to benefit—most manufacturing job losses have come from mechanization rather than outsourcing, and have been offset by new jobs in other sectors).

Thanks to trade and exchange, people in all income percentiles have made real gains, and living standards for the middle class in advanced economies have soared in ways not captured by looking at income alone. America’s middle class is getting richer, and the people in the world’s 75th to 90th income percentiles are also winners.

Chelsea Follett is the Managing Editor of HumanProgress.org, a project of the Cato Institute which seeks to educate the public on the global improvements in well-being by providing free empirical data on long-term developments. Her writing has been published in the Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, and Global Policy Journal. She earned a Bachelor of Arts in Government and English from the College of William & Mary, as well as a Master of Arts degree in Foreign Affairs from the University of Virginia, where she focused on international relations and political theory.

This work by Cato Institute is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.