Venezuela’s Bizarre System of Exchange Rates – Article by Emiliana Disilvestro & David Howden

Venezuela is currently going through its worst crisis in history, replete with an endless list of interesting problems. Foremost among these are severe shortages in even the most basic of necessities. Economists have used these shortages as textbook examples to illustrate the pernicious effects of price controls.

Few people, however, are aware that many of the country’s problems are caused by a complex monetary arrangement that makes use of four different exchange rates simultaneously. The result is that Venezuela can either be extremely cheap, or unbearably expensive, depending on the rate used.

Monetary chaos began in 2003 when the late President Hugo Chavez imposed currency controls to stem capital flight after an oil strike. At the time, one US dollar could fetch 1.6 Venezuelan bolivars. Today, barely ten years later, that same dollar can buy 172 bolivars, a devaluation of over 99 percent! Of course, that is in the official (i.e., government regulated) market. On the black market, the exchange rate is currently nearly 900 bolivars to the US dollar. That is, if you can find anyone selling dollars, or more importantly, looking to buy the badly tarnished Venezuelan currency.

This devaluation is in and of itself a large problem, both for consumers who must deal with high degrees of price inflation and for businesses that must undergo long-term capital planning decisions with a constantly moving monetary unit. However, it is the volatility of the exchange rate caused by the government’s continuous changes to currency restrictions and official rates that is proving the most cumbersome problem.

A Very Complex System of Exchange Rates

Currently there are four exchange rates: First is the official one, called CENCOEX, and which charges 6.30 bolivars to the dollar. It is only intended for the importation of food and medicine.

The next two exchange rates are SICAD I (12 bolivars per dollar) and SICAD 2 (50 bolivars per dollar); they assign dollars to enterprises that import all other types of goods. Because of the fact that US dollars are limited, coupons are auctioned only sporadically; usually weekly in the case of SICAD 1 and daily for SICAD 2. However, due to the economic crisis, no dollars have been allocated for these foreign exchange transactions and there hasn’t been an auction since August 18, 2015. As of November 2015, the Venezuelan government held only $16 billion in foreign exchange reserves, the lowest level in over ten years, and an amount that will dry up completely in four years time at the current rate of depletion.

The last and newest exchange rate is the SIMADI, currently at 200 bolivars per dollar. This rate is reserved for the purchase and sale of foreign currency to individuals and businesses.

There are many problems in Venezuela as a result of this complex system. The most obvious is the near impossibility to actually get assigned to these rates due to the complex bureaucratic process one must navigate to apply for them. In response to these difficulties, Venezuelans must rely on the black market to meet their demands for foreign currency. Therefore, people naturally rely on the black market rate, which although it is much less advantageous (at 900 vs. anywhere from 6.3 to 200 bolivars per dollar on the “official” market), at least offers the possibility to procure the much needed foreign exchange.

Corruption, which is a main characteristic of Venezuela’s political regime, is another problem derived from this complex monetary system. Officials within the government and those connected to it have taken advantage of their positions of power and influence to mismanage the money assigned for other, productive and necessary, institutions. Thus, well-connected individuals obtain US dollars through the legal channels and then sell them on the black market at a higher price. (This activity is one of the only ways to consistently earn high levels of profits in the beleaguered Venezuelan economy, and is only available to those privileged few who are connected to the proper government officials.)

This point is especially important when studying the vast array of shortages. The embezzlement of foreign currency intended for importing basic goods, e.g., foreign exchange reserved for the CENCOEX and SICAD exchange rates, leave legitimate businessmen with no options to obtain legally the necessary currencies to import goods. Owing to the rapidly depreciating bolivar, US dollars are hoarded as a means of savings, thus further exacerbating the foreign exchange shortage for importers. As a consequence, imports are unable to be paid for, leading to shortages on top of those already caused by extensive and damaging price controls.

The Poor Suffer the Most

These problems affect directly all citizens, but are especially pernicious to lower-income individuals. Many suppliers will only sell what few goods they have for US dollars, eschewing accepting bolivars in the payment of their wares. Black market currency sellers set up shop outside supermarkets to accommodate this phenomenon, but it must be noted that only the upper-middle and higher income earners are able to afford to pay the black market rate. The result is that the lower-income segment of Venezuelan society, those who price and currency controls are supposedly helping, are not able to obtain the currency necessary to buy simple goods and services (and the wealthy can only do so at a high price).

Although the business community demands to be paid in US dollars this harms lower-income individuals unduly and is a completely rational response. If businesses kept selling their scarce supply of goods at the official rate their shelves would deplete faster than they already do. Venezuelans earn income at the official rate of 6.30 bolivars to the US dollar while businesses must pay a much higher rate in order to import goods. This difference must be accounted for by stores asking for prices commensurate with what they must pay to stock their shelves.

The complex exchange rate system in Venezuela is not only a good example of unnecessary government meddling in the economy, but also explains why a corrupt political regime has been able to retain power for so long despite more than a decade of hardship imposed on the country. The use of several exchange rates has made it easy for the Chávez and Maduro governments and their followers to make enormous profits by embezzling the money assigned to the business community and individuals. By doing so, they have completely devalued the bolivar and impoverished what was once one of the richest countries in the world.

Emiliana Disilvestro studies international business at Saint Louis University at its Madrid campus.

David Howden is Chair of the Department of Business and Economics and professor of economics at St. Louis University’s Madrid Campus, and Academic Vice President of the Ludwig von Mises Institute of Canada.

This article was published on Mises.org and may be freely distributed, subject to a Creative Commons Attribution United States License, which requires that credit be given to the author.

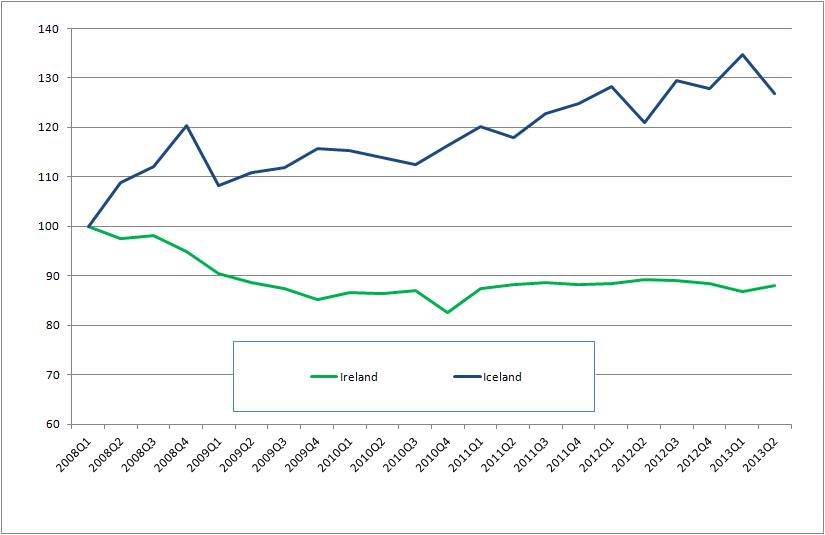

Figure 1: Nominal GDP (2008 = 100) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

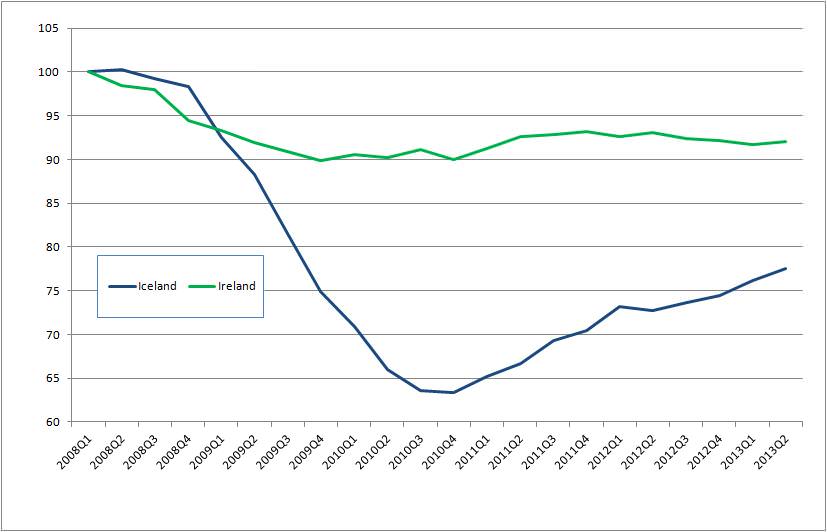

Figure 1: Nominal GDP (2008 = 100) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Figure 2: Real GDP (2008 = 100) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

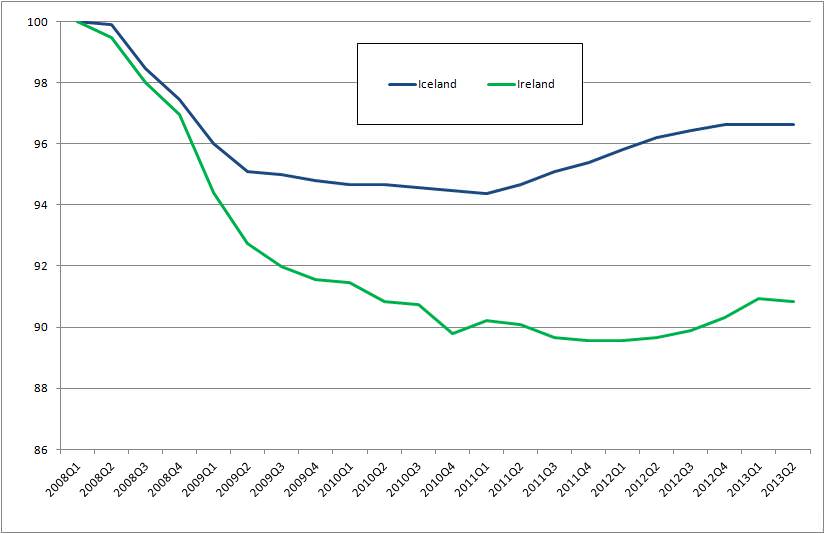

Figure 2: Real GDP (2008 = 100) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Figure 3: Employment rate (2008 = 1) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

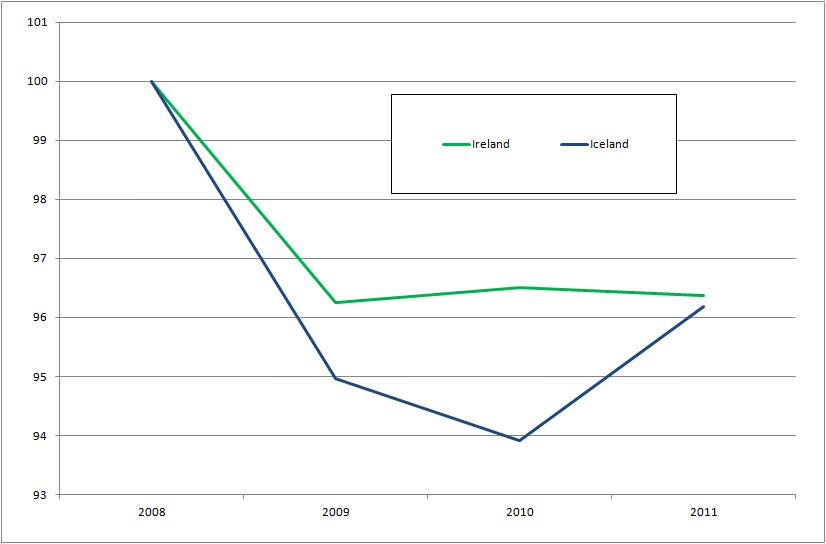

Figure 3: Employment rate (2008 = 1) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Figure 4: Annual hours worked (2008 = 100) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Figure 4: Annual hours worked (2008 = 100) Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis