Our Economic Malaise Is Impacting Young Workers the Most – Article by Ryan McMaken

Ryan McMaken Comments 0 Comment

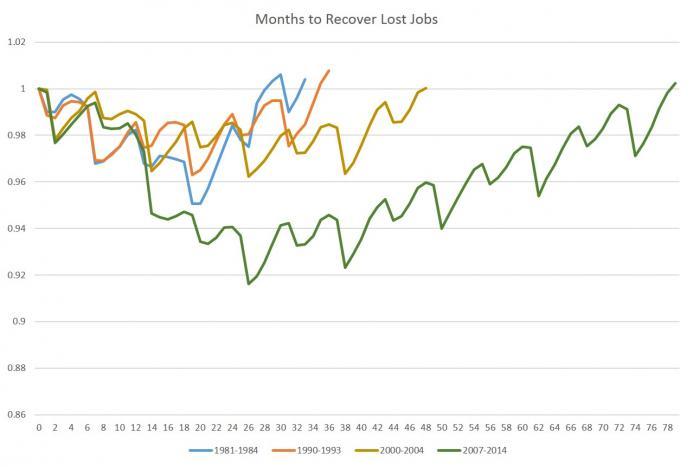

In the wake of the 2007-2009 recession, 78 months passed before employment returned to where it had been before the crisis. This was, by far, the longest period needed to recover from job losses in decades. The second-longest period needed to recover jobs occurred after the 2002 recession when about 50 months were needed to recover lost jobs:

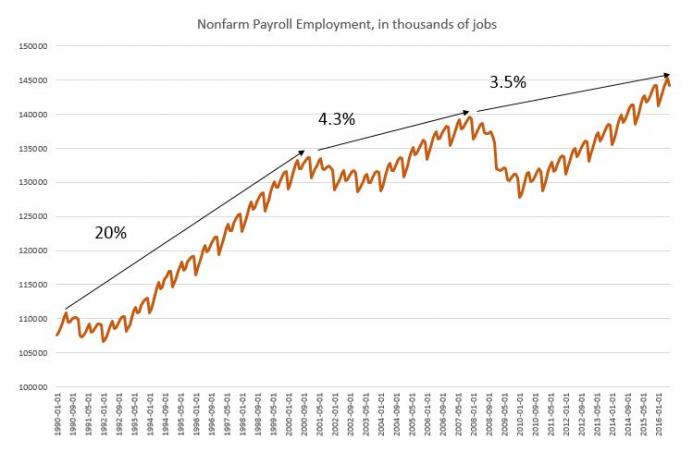

Moreover, we see that in recent cycles, job growth during each recovery has been getting weaker and weaker over time:

Some observers of the rose-colored-glasses-wearing variety have attempted to explain away the most recent malaise in job gains by claiming that fewer jobs are needed because so many Baby Boomers are aging out of the work force, and because people are so much wealthier, they argue, workers are leaving the labor force for non-economic reasons. That is, people are leaving the labor force for reasons other than being discouraged workers.

These claims are plausible, but the empirical data we have does not support them.

Keep in mind that ever since the 2007-2009 recession, the U-6 unemployment rate, which includes underemployed workers (i.e., involuntary part timers) and discourage workers, has reached multi-decade highs in recent years, and even now, is only at levels seen during the worst of the last recession:

This is not simply a matter of fewer jobs being created because workers are going away.

To get a sense of the situation, we have to first look at the demographics of the working age population and the labor force.

(This demographic data on the working-age population is only currently available through the first quarter of 2015, so the time series ends in early 2015.)

The top line is the total working age population (ages 15-65) published by the OECD and the World Bank. According to this measure, there is no decline in the working age population.

If people were aging out of the work force in droves to the point of driving a net exodus, we would see a downturn in the blue line. We don’t see that. In fact, from the beginning of the last recession at the end of 2007 to the first quarter of 2015, the working age population increased by 7.5 million people.

During that same period, the US economy added 801,000 jobs. That is, after the initial loss of 10 million jobs, the US economy began to add jobs again, but after more than seven full years, had only added a net of 801,000 jobs.

But maybe only 801,000 jobs were added because very few of those 7.5 million people wanted to be in the work force.

Well, it’s a safe bet that not all of them wanted to be in the work force, but we do know that using the standard BLS measure for the work force that 2.4 million people entered the work force during the period when only 801,000 jobs were added. (See the green line above.) That means over that time period, you had 1.6 million new people in the labor force while half that many jobs were added.

And this labor force measure only takes into account active job seekers and employed people. It ignores discouraged workers and involuntary part timers.

So we find that both the official labor force and the working age population were increasing at levels substantially above the employment levels.

Indeed, the only way we can find a number that suggests more jobs were added than workers is to look at the working-age population for ages between 25 and 54. That is, if we exclude all potential workers under 25 and all above 54, then yes, the working age population did decline by 1 million jobs. (See the red line above.)

In real life, though, the work force includes quite a few people who are, say, 22 years old, and quite a few who are 60 years old. If those people are included, the working age population is growing considerably.

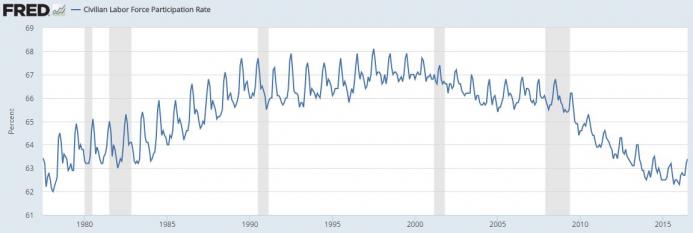

Meanwhile, workforce participation has been falling for a number of years, and is now at some of the lowest levels that have been seen in more than 30 years. From 2014 to 2016, work force participation ranged from about 62 percent to 64 percent. That’s the lowest participation rate seen since the the early 1980s.

Many have assumed this means that many older workers are leaving the work force. Unfortunately, it seems that it is young workers who are most likely to leave the labor force, which is problematic for future productivity. For young workers in the 20-24 age range, work force participation has been falling for more than a decade, and fell off significantly during the last recession:

Meanwhile, labor force participation for 55-and-older individuals has held steady:

It appears unlikely that it is now unnecessary to add jobs at a rate comparable to past recoveries because so many older workers are leaving the work force. Nor is it likely that young people are leaving the work force because they are so prosperous. It’s more likely that young people are leaving the work force as discouraged workers.

This supposition is further strengthened by the fact that the unemployment rate in the 16-24 age range has been above 10 percent for the past nine years. It was especially high even before the last recession.

But, unemployment among over-55 workers is among the lowest of all demographic groups, with a rate between 3 percent and 4 percent in recent years.

In other words, older workers are sticking around and doing relatively well. It appears that younger workers, meanwhile, are more likely to be unemployed, underemployed, or even totally out of the workforce as discouraged workers.

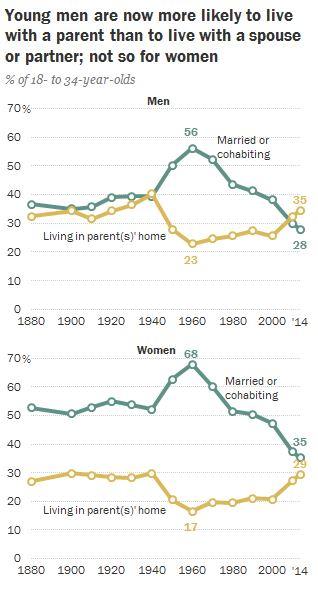

One phenomenon that gives us a reason to think this is the fact that the number of young people living with their parents has reached historic highs in the United States. As Pew recently reported:

In 2014, for the first time in more than 130 years, adults ages 18 to 34 were slightly more likely to be living in their parents’ home than they were to be living with a spouse or partner in their own household.

Living at home is more likely for men than for women, but in both cases, more young people are living with their parents than during any other period since World War II:

Those who attempt to spin the current job numbers as simply the effects of people happily leaving the work force appear to be mistaken in assuming that older workers are leaving, and that younger workers need not work because they’re so unusually productive.

If young workers were so productive, is it too much to believe that they would choose to rent an apartment rather than live with their parents?

Once we look a the demographics behind the current job numbers, we actually find the situation is more alarming that we might have thought otherwise. We seem to be in a situation where younger workers are participating in the work force less, and putting off acquiring essential job skills that will lead to more productivity later.

Older workers are still sticking around in numbers large enough to keep the overall labor force number growing.

However, while both the working age population and the labor force are growing, overall job creation simply is not keeping up.

At some point, those 30-year olds living with their parents are doing to need full-time work, but will they have the job experience necessary (and thus the productivity) necessary to support the lifestyle to which they have become accustomed?

Or, will they simply enter the workforce with few job skills following a decade of part-time work or no work forced on them by our weak economy? When that happens, we’re likely to see a continued decline in the household and personal incomes.

Ryan W. McMaken is the editor of Mises Daily and The Free Market. He has degrees in economics and political science from the University of Colorado, and was the economist for the Colorado Division of Housing from 2009 to 2014. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

This article was published on Mises.org and may be freely distributed, subject to a Creative Commons Attribution United States License, which requires that credit be given to the author.