The Fed Desperately Tries to Maintain the Status Quo – Article by Ronald-Peter Stöferle

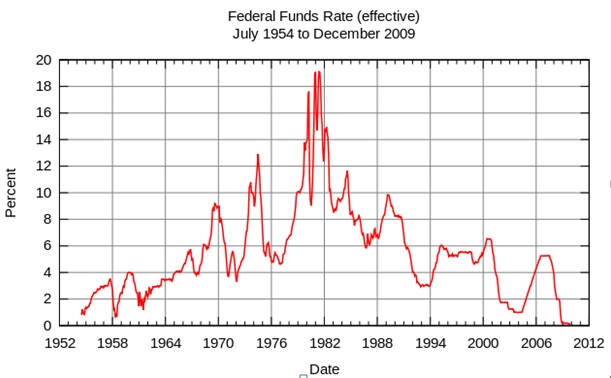

During the press conferences of recent FOMC meetings, millions of well-educated investment professionals have been sitting in front of their screens, chewing their fingernails, listening as if spellbound to what Janet Yellen has to tell them. Will she finally raise the federal funds rate that has been zero bound for over six years?

Obviously, each decision is accompanied by nervousness on the markets. Investors are fixated by a fidgety curiosity ahead of each Fed decision and never fail to meticulously observe Janet Yellen and the FOMC, and engage in monetary ornithology on doves (growth- and employment-oriented FOMC members) and hawks (inflation-oriented FOMC members).

Fed watchers also hope for some enlightening information from Ben Bernanke. According to Reuters, some market participants paid some $250,000 just to join one of several dinners, where the ex-chairman spilled the beans. Apparently, he does not expect the federal funds rate to return to its long-term average of about 4 percent during his lifetime.

In a conversation with Jim Rickards, Bernanke stated that a rate hike would only be possible in an environment in which “the U.S. economy is growing strongly enough to bear the costs of higher rates.” Moreover, a rate increase would have to be clearly communicated and anticipated by the markets — not to protect individual investors from losses, Bernanke assures us, but rather to prevent jeopardizing the stability of the “system as a whole.”

It is axiomatic that zero-interest-rate-policy (ZIRP) cannot be a permanent fixture. Indeed, Janet Yellen has been going on about increasing rates for almost two years now. But, how much more lead time will it require to “prepare” the markets? In both September and October the FOMC chickened out, even though we are not talking about hiking the rate back to “monetary normalcy” in one blow. The decision on the table is whether or not to increase the rate by a trifling quarter point!

The Fed’s quandary can be understood a little better by examining what “monetary normalcy,” or a “normal interest rate,” is supposed to be. Or, even more fundamentally: what is an interest rate?

We “Austrians” understand an interest rate as an expression of market participants’ time preference. The underlying assumption is that people are inclined to consume a certain product sooner rather than later. Hence, if savers restrict their current consumption and provide the resources for investment instead, they do so only on condition that they will be compensated by increased opportunities for consumption in the future. In free markets, the interest rate can be regarded as a measure of the compensation payment, where people are willing to trade present goods for future goods. Such an interest rate is commonly referred to as the “natural interest rate.” Consequently, the FOMC bureaucrats would ideally set as a goal a “normal interest rate” that equals the “natural” one.This, however, remains unlikely.

Six Years of “Unconventional” Monetary Policy

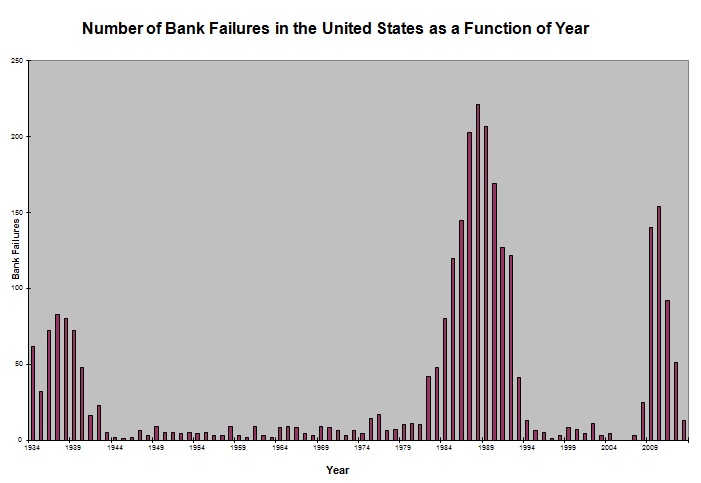

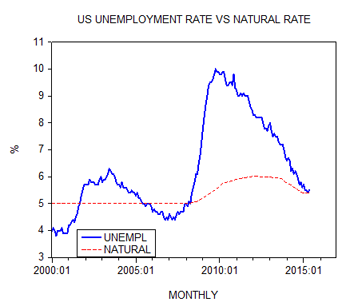

ZIRP was introduced six years ago in response to the financial crisis, and three QE programs have been conducted. This so-called “unconventional monetary policy” is supposed to be abandoned as soon as the economy has gathered pace. Despite the tremendous magnitude of these market interventions, the momentum in the US economy is rather lame. Weak Q1 data, which probably resulted from a weak trade balance due to a 15 percent rise of the US dollar, shocked even the most pessimistic of analysts; the OECD and the IMF have revised down their 2015 growth estimates. A long-lasting, self-sustaining growth is out of the question. This confirms the assumption that ZIRP fuels everything under the sun — see “The Unseen Consequences of Zero-Interest-Rate Policy” — except long-term productive investment.And what about unemployment and inflation that are key elements of the Fed’s mandate? The conventional unemployment rate (U3) has returned to its long-run normal level, so the view prevails that things are developing well. However, those figures conceal a workforce participation rate that has fallen by more than 3 percent since 2008, indicating that some 2.5 million Americans are currently no longer actively looking for a new job. However, should the economic situation improve, they would likely rejoin the labor force. Furthermore, the proportion of those only working part-time due to a lack of full-time positions is much higher now than before the crisis. “True” unemployment currently stands rather at about 7.25 percent.

A Weak Economy and Weak Inflation

With regard to inflation, the Fed’s target is 2 percent, as measured by growth of the PCE-index. This aims to buffer the fiat money system against the threat of price deflation. In a deflationary environment, it is believed, the debt-servicing capacity of market participants (e.g., governments, private enterprises, financial institutions, and private households) would come under intense pressure and likely trigger a chain reaction in which loans collapse and the monetary system implodes.

In many countries, and among them the US, inflation is remarkably low — partly due to transitory effects of lower energy and import prices — while low interest rates have merely weaved their way to asset price inflation so far. But, as price reactions to monetary policy maneuvers may occur with a lag of a few years, we should expect that sooner or later inflation will also spill over to normal markets.

As a response to anything short of massive improvement of economic and employment data, a rate hike is scarcely likely, and inflation in the short-term is also unlikely. Moreover, the current composition of the FOMC — which is extremely dovish — implies inflation-sensitive voices are relatively underrepresented. This gives rise to the suspicion that rate hikes are not very likely at all in the scenario in the short-term.

What Will the Fed Do If There’s Real Economic Trouble?

One is concerned about economic development, which has a shaky foundation and headwinds from other parts of the world; it appears that growth has cooled down substantially in the BRICS countries. Meanwhile, China might be on the brink of a severe recession. (Indeed, China was possibly the most decisive factor to nudge the Fed away from raising rates in September and October.) This implies that world-wide interest rates will remain at very low levels and a significant rate hike in the US would represent a sharp deviation in this environment, bringing with it massive competitive disadvantages.

The markets are noticeably pricing out a significant rate hike. The production structure has long since adapted to ZIRP and “short-term gambling, punting on momentum-driven moves, on levered buybacks” are further lifting the opportunity costs of abandoning it. In order to try to rescue its credibility, the Fed may decide to try some timid, quarter-point increases.

But what will they do if markets really crash? Indeed, they are terrified of the avalanche that they might trigger. If there are any symptoms that portend calamity, the Fed will inevitably return to ZIRP, launch a QE4, or might even introduce negative interest rates. Hence, there does not seem to be a considerable degree of latitude such that a return to conventional monetary policy could seriously be expected.

“The Fed is raising rates!” — This has become a running gag.

Ronald-Peter Stöferle is a Chartered Market Technician (CMT) and a Certified Financial Technician (CFTe). During his studies in business administration and finance at the Vienna University of Economics and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, he worked for Raiffeisen Zentralbank (RZB) in the field of Fixed Income/Credit Investments. In 2006 he began writing reports on gold. His six benchmark reports called “In GOLD we TRUST” drew international coverage on CNBC, Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal, The Economist and the Financial Times. He was awarded “2nd most accurate gold analyst” by Bloomberg in 2011.

This article was originally published by the Ludwig von Mises Institute. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided full credit is given.

Does Demand Create More Supply?

Does Demand Create More Supply?

Production Comes Before Demand

Production Comes Before Demand