4 Ways Employers Respond to Minimum Wage Laws (Besides Laying Off Workers) – Article by John Phelan

John Phelan

September 25, 2019

*************************

Most of you will be familiar with a supply and demand graph. This shows a demand curve, which graphs the relationship between the price of something and the quantity demanded of that something, as well as a supply curve, which graphs the relationship between the price of something and the quantity supplied of that something. It is probably the most basic—and useful—model in economics. Whether the something in question is a good or a service, shoes or labor, the basic supply and demand model predicts that, ceteris paribus, an increase/fall in the price of something will lead to a fall/increase in the quantity demanded of that something—this is Econ 101.

Whether the something in question is a good or a service, shoes or labor, the basic supply and demand model predicts that, ceteris paribus, an increase/fall in the price of something will lead to a fall/increase in the quantity demanded of that something—this is Econ 101.

In the context of minimum wage laws, this model predicts that setting a minimum wage above the equilibrium level or raising it will lead to a lower quantity of labor demanded. Often, people think this means fewer workers employed. So, when minimum wage hikes aren’t followed by increases in unemployment, people cite this as evidence that minimum wage hikes don’t reduce employment.

But a model is an abstraction from reality. In that messy reality, there are a number of things employers can do in response to a minimum wage hike that don’t involve laying off employees.

Cut Hours Rather Than Workers

Remember, the simple supply and demand model says that increasing the price of labor leads to a lower quantity of labor demanded. But an employer doesn’t need to cut workers to achieve that. They can cut their hours instead.

Research from Seattle illustrates this. In 2014, the city council there passed an ordinance that raised the minimum wage in stages from $9.47 to $15.45 for large employers in 2018 and $16 in 2019. In 2017, research from the University of Washington examining the effects of the increases from $9.47 to as much as $11 in 2015 and to as much as $13 in 2016, found:

…the second wage increase to $13 reduced hours worked in low-wage jobs by around 9 percent, while hourly wages in such jobs increased by around 3 percent. Consequently, total payroll fell for such jobs, implying that the minimum wage ordinance lowered low-wage employees’ earnings by an average of $125 per month in 2016. [This was later revised to $74]

As the model predicts, the price of labor increased, and the quantity of labor demanded fell.

A follow-up paper looked at the impact on workers who were employed at the time of the wage hike, splitting them into experienced and inexperienced workers. It found that, on average, experienced workers earned $84 a month more, but about a quarter of their increase in pay came from taking additional work outside Seattle to make up for lost hours. Inexperienced workers, on the other hand, got no real earnings boost—they just worked fewer hours. Again, as the model predicts, the price of labor increased and the quantity of labor demanded fell. Instead of more money, they got more free time.

Make Employees Work Harder

An employer could try to raise worker productivity to match the new minimum wage. One way to do this is simply to work their employees harder.

One paper by Hyejin Ku of University College London looks at the response of effort from piece-rate workers who hand-harvest tomatoes in the field to the increase in Florida’s minimum wage from $6.79 to $7.21 on January 1, 2009. It found that worker productivity (i.e., output per hour) in the bottom 40th percentile of the worker fixed effects distribution increases by about 3 percent relative to that in the higher percentiles. The author concludes:

These findings suggest that while an exogenously higher minimum wage implies a higher labor cost for the firm, the rising cost can be partly offset by the increased effort and productivity of below minimum wage workers.

Another recent study by economists Decio Coviello, Erika Deserranno, and Nicola Persico looks at the impact of a minimum wage hike on output per hour among salespeople from a large US retailer. “We find that a $1 increase in the minimum wage (1.5 standard deviations) causes individual productivity (sales per hour) to increase by 4.5%,” they note.

Importantly, tomato harvesting and sales are labor-intensive work. Any increase in output per hour can be assumed to come from increased physical effort.

Cut Other Elements of Remuneration

Supporters of higher minimum wages talk almost exclusively about wages. But this is only one part of a worker’s total remuneration. The cost of an employee to the employer is not just the wage but total remuneration, including benefits such as health insurance. If legislation increases the wage, the employer can keep overall remuneration the same by reducing other elements.

A new paper from economists Jeffrey Clemens, Lisa B. Kahn, and Jonathan Meer finds that this is what happens in practice. The authors “explore the theoretical and empirical relationship between the minimum wage and fringe benefits, with a focus on employer-sponsored health insurance.” They find:

[There is] robust evidence that state-level minimum wage changes decreased the likelihood that individuals report having employer-sponsored health insurance. Effects are largest among workers in very low-paying occupations, for whom coverage declines offset 9 percent of the wage gains associated with minimum wage hikes. We find evidence that both insurance coverage and wage effects exhibit spillovers into occupations moderately higher up the wage distribution. For these groups, reductions in coverage offset a more substantial share of the wage gains we estimate.

Simply put, as the minimum wage rises, other elements of worker compensation fall.

Hire Fewer People, More Robots

If a business that plans to add 10 jobs over a year cancels these plans on the passage of a minimum wage hike, those 10 jobs have been destroyed without ever showing up in the data.

Economists from Washington University in St. Louis use wage data on one million hourly wage employees from over 300 firms spread across 23 two-digit NAICS industries to estimate the effect of six state minimum wage changes on employment. They find “…that firms are more likely to reduce hiring rather than increase turnover, reduce hours, or close locations in order to rebalance their workforce.”

As we look at responses over time, we also see the possibility that employers can substitute capital inputs for labor inputs.

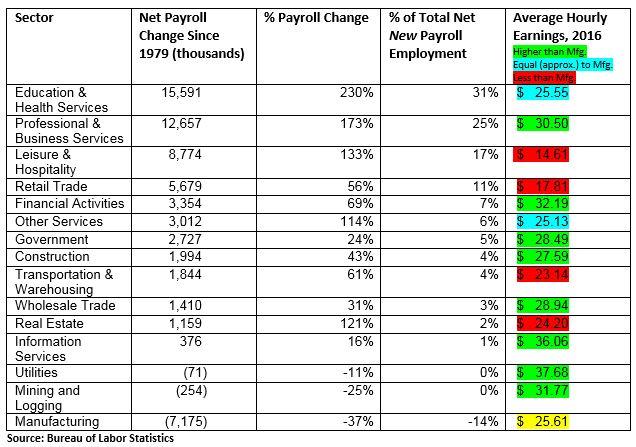

Economists Grace Lordan and David Neumark analyze how changes to the minimum wage from 1980 to 2015 affected low-skill jobs in various sectors of the US economy, focusing particularly on “automatable jobs – jobs in which employers may find it easier to substitute machines for people,” such as packing boxes or operating a sewing machine. They find that across all industries they measured, raising the minimum wage by $1 equates to a decline in “automatable” jobs of 0.43 percent, with manufacturing even harder hit.

They conclude that

groups often ignored in the minimum wage literature are in fact quite vulnerable to employment changes and job loss because of automation following a minimum wage increase.

Minimum wage hikes are bad public policy. Economics, like all social sciences, has difficulty testing its models against data, but even where we can, the evidence bears this out.

John Phelan is an economist at the Center of the American Experiment and fellow of The Cobden Centre.

This article was originally published by the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE).