The Aristotelian Golden Mean as Conducive to Good Health in the Pursuit of Life Extension – Article by G. Stolyarov II

“By the mean of a thing I mean what is equally distant from either extreme, which is one and the same for everyone; by the mean relative to us what is neither too much nor too little, and this is not the same for everyone. For instance, if ten are many and two few, we take the mean of the thing if we take six; since it exceeds and is exceeded by the same amount; this then is the mean according to arithmetic proportion. But we cannot arrive thus at the mean relative to us. Let ten lbs. of food be a large portion for someone and two lbs. a small portion; it does not follow that a trainer will prescribe six lbs., for maybe even this amount will be a large portion, or a small one, for the particular athlete who is to receive it…. In the same way then one with understanding in any matter avoids excess and deficiency, and searches out and chooses the mean — the mean, that is, not of the thing itself but relative to us.”

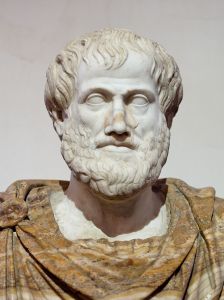

~ Aristotle (384-322 BCE), Nicomachean Ethics, 1106a29-b8

This is not medical advice, but rather a general synthesis of philosophical and common-sense lifestyle heuristics for those who are generally healthy and seek to stay that way for as long as possible. All of the ideas below are ones I endeavor to put into practice personally as part of my endeavor to survive long enough to benefit from humankind’s future attainment of longevity escape velocity and indefinite lifespans. As an educated layman, not a medical doctor, I accept contemporary “mainstream” medicine (i.e., evidence-based, scientific medicine) as the most reliable guidance for specific health matters that currently exists. I consider the discussion below to be sufficiently general and basic as to be consistent with common medical knowledge – though, in any particular person’s case, specific medical advice should prevail over anything to the contrary in this essay.

It is easier for humans to live by absolutes than by degrees. If a practice or pursuit is unambiguously harmful, it can readily be avoided. If it is unambiguously beneficial, then it can be pursued in any quantity permitted by one’s available time and other resources. The very fact of being alive is itself an unambiguous good, of which no amount is excessive. On the other hand, death of the individual is an unambiguous harm, as is any behavior that directly precipitates or hastens death due to harmful effects upon the human body.

But much of life is comprised of elements that are essential to human well-being in some quantity but could become harmful if pursued to excess. This is where Aristotle’s idea of the “golden mean” – of virtue as being neither a deficiency nor an excess of various necessary attributes – can be applied to the pursuit of health and longevity. Indeed, much of health consists of maintaining key bodily functions and metrics within favorable ranges of parameters. A healthy weight, healthy blood-sugar concentration, healthy blood pressure, and a healthy heart rate all exist as segments along spectra, bordered by other segments of deficiency and excess.

More is known today about what is harmful to longevity than what would extend it past today’s typical “old age”. For instance, smoking, consumption of most alcohol (apart, possibly, from modest quantities of red wine), and use of many recreational drugs are clearly known to increase mortality risk. As these habits provide no support for any essential life function while having the potential to cause great harm to health, it is best to eschew them altogether. Indeed, the mere avoidance of all tobacco use is statistically the single best way to increase one’s remaining life expectancy. Yet this is the easy part, as one can quite resolutely and immoderately reject all consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drugs with no harm to oneself and only benefits.

An Aristotelian “golden mean” approach is needed, on the other hand, for those elements which are indispensable to sustaining good health, but which can also damage health if indulged in imprudently and to excess. Aristotle recognized that the “golden mean” when it comes to individual behavior cannot be derived through a strict formula but is rather unique to each person. Still, its determination is based on objective attributes of physical reality and not on one’s wishes or on the path of least resistance. The realms of diet, exercise, and supplementation are of particular relevance to life extension. It would particularly benefit individuals who seek to extend their lives indefinitely to adopt “golden mean” heuristics in each of these realms, until medical science advances sufficiently to develop reliable techniques to reverse biological senescence and greatly increase maximum attainable lifespans.

Food

Food is sustenance for the organism, and its absence or deficiency lead to starvation and malnutrition. Its excess, on the other hand, can lead to obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and a host of associated ills. It is clear that a moderate amount of food is desirable – one that is enough to sustain all the vital functions of the organism without precipitating chronic diseases of excess. Contrary to common prejudice, it is not too difficult to gain a reasonably good idea of the quantity of food one should consume. For most people, this is the quantity that enables an individual to maintain weight in the healthy range of body-mass index (BMI). (There are exceptions to this for certain athletes of extraordinary muscularity, but not for the majority of people. Contrary to common objections, while it is true that BMI is not the sole consideration for healthy body mass, it is a reasonably good heuristic for most, including many who are likely to object to its use.)

The comparison of “calories in” versus “calories out” – even though it must often rely on approximation due to the difficulty of exactly measuring metabolic activity – is nevertheless quite dependable. It is scientifically established that consuming a surplus of 3,500 calories (over and above one’s metabolic expenditures) results in gaining one pound (0.45 kilograms) of mass, whereas running a deficit of 3,500 calories results in the loss of one pound.

Consuming a moderate amount of food (relative to one’s exercise level) to maintain a moderate amount of weight is one of the most obvious applications of the principle of the golden mean to diet. Yet it is also the composition of one’s food that should exhibit moderation in the form of diversification of ingredients and food types.

Principle 1: There are no inherently bad or inherently good foods, but some foods are safer in large amounts than others. (For instance, eating a bowl full of vegetables is safer than eating a bowl full of butter.) Furthermore, one’s diet should not be dominated by any one type of food or any one ingredient.

Principle 2: In order to maintain a caloric balance at a healthy weight, consideration of calorie density of foods is key for portion sizes. More calorie-dense foods should be consumed in smaller portions, while less calorie-dense foods could be consumed in larger portions, provided that there is adequate diversification among the less calorie-dense foods as well.

Here my approach differs immensely from any fad diet – from veganism to the paleo diet to anything in between that prescribes a list of mandatory “good” foods and forbidden “evil” foods and attempts to rule human lives through minute regimens of cleaving to the mandatory and eschewing the forbidden. I acknowledge that virtually any fad diet is superior to unrestrained gluttony or the unconscious, stress-induced lapses into unhealthy eating that plague many in the Western world today. This, indeed, is the reason for such diets’ popularity and the availability of “success stories” from among practitioners of any such diet: virtually any conscious control over food intake and concern over food quality is superior to sheer abandon. However, all fad diets are also pseudo-scientific. Contradictory evidence regarding the health effects of almost any type of food – from meat to bread to chocolate to salt and even large quantities of fruits and vegetables – emerges in both scientific and popular publications every week. While some approaches to diet are clearly superior to others (e.g., most diets would be superior to a candy-only diet or a diet consisting solely of peas, as in Georg Büchner’s play Woyzeck), no fad diet can claim to reliably extend human lifespans beyond average life expectancies in the Western world today.

In the absence of clear, scientific evidence as to the unambiguous benefits or harms of any particular widely consumed food, diversification and moderation offer one the best hope of maximizing one’s expected longevity prior to the era of rejuvenation therapies. This is because of two key, interrelated effects:

Effect 1: If some food types indeed convey particularly important health benefits, then diversification helps ensure that one is gaining these benefits as a result of consuming at least some foods of those types.

Effect 2: If some foods or food types indeed result in harms to the organism – either due to the inherent properties of these foods or due to dangers introduced by the specific ways in which they are cultivated, delivered, or improperly preserved – then diversification helps reduce the organism’s exposure to such harms arising from any one particular food or food type, therefore lessening the likelihood that these harms will accumulate to a critical level.

Diversification, coupled with consideration of calorie density of foods, has the additional advantage of flexibility. If one encounters a situation where dietary choice is inconvenient, one might still enjoy the occasion and accommodate it through judicious portion sizing or adjustments to other meals either beforehand or afterward. One does not need to condemn oneself for having committed the dietary sin of eating an “unhealthy food” – as it is not the food itself that is unhealthy, but rather the frequency and amounts in which it is consumed. The Aristotelian “golden mean” heuristic also implies that there is no fault with pursuing food for the purpose of enjoyment or sensory pleasure – again, in moderation, as long as no detriment to health results.

A final note on diet is that the approach of moderation does not favor caloric restriction – i.e., reduction in calorie intake far below typical diets that suffice for maintaining a healthy body mass. Caloric restriction has shown remarkable effects in increasing lifespans in simple organisms – yeast, roundworms, and rodents – but has not demonstrated significant longevity benefits for humans, at least as suggested by presently available research. It is possible that the positive effects which caloric restriction confers upon simpler organisms are already reaped by humans and higher animals to a great extent, such that any added benefits to these organisms’ already far longer lifespans would be slight at best. A calorie-restricted diet is an excellent option for those seeking to lose weight or transition from a diet of gluttony and reckless abandon. It is also likely superior to “average” dietary habits today in terms of forestalling diet-related chronic diseases. However, there is no compelling evidence at present that a calorie-restricted diet is superior to a moderate, diversified diet that maintains a caloric balance. Furthermore, extreme calorie restriction would either require activity restriction (to conserve energy) or would involve descending into an underweight range, which is associated with its own health risks.

Exercise

Exercise cannot be disentangled from considerations of dietary choice, since it is crucial to the expenditure side of the caloric equation (or inequality). It is, again, scientifically incontrovertible that regular exercise is superior to a sedentary lifestyle in enhancing virtually every metric of bodily health. On the other hand, moderation should be practiced in the degree of physical exertion at any given time, so as to prevent pushing one’s body to its breaking point – which will differ by individual. Exercising in such a manner that gradually pushes one’s sphere of abilities outward will help render the probability of reaching a breaking point – the failure of any bodily system – increasingly remote. For instance, gradually building up one’s running ability can eventually enable one to run an ultramarathon without adverse consequences. However, if an overweight and completely sedentary person were to attempt to run an ultramarathon without any prior running experience (and did not give up after a few miles), the results would be disastrous. Likewise, it is possible to lift large weights safely, but only if one begins with smaller weights and gradually works one’s way up.

For virtually all individuals in the Western world today, no harm can arise from the increase in the absolute amount of physical activity, as long as the exercise is performed in a safe environment and with safe form. Immoderate kinds of exercise would include extreme sports (those which entail a significant danger to life), any sports in extreme weather, or any exertion at the boundary of the current tolerance of one’s heart and other muscles. Most people, however, can easily find activities – ranging from simple walking to light lifting and body-weight exercises – that would pose no such risks and would unambiguously improve health.

Diversification in exercise, as with diet, is superior to exclusivist fad regimens. While any safe exercise is superior to none, it is completely unfounded to insist that only one particular type or genre of exercise is “good” while all the others are “bad”. The currently fashionable “no cardio” camp is a particularly glaring example of absurdity in this regard, eschewing some of the most effective ways possible for burning calories, maintaining cardiovascular and muscular health, and preventing diabetes and many types of cancer. But it would be similarly unreasonable to reject all weight lifting or all flexibility training due to some dogma regarding “ideal” kinds of exercise. It is best to perform a variety of exercises, each of which emphasize different facets of health. That being said, the exact mix would depend on the attributes and preferences of a given individual, and appropriate diversification could still involve a heavily emphasized preferred type of exercise, in addition to various auxiliary types that enable one to also improve in other areas.

Again, it is important to emphasize that, while regular exercise can improve one’s likelihood of surviving to current “old age”, it cannot, by itself, protect against the ravages of senescence beyond perhaps slightly deferring them. The best case for regular, moderate exercise is that it can raise one’s chances of surviving to an era when medical treatments that reverse biological senescence will become available and widespread.

Because exercise should be pursued with the intention of maximizing health and improving one’s likelihood of long-term survival, great care must be taken not to allow the competitive aspects of any exercise to overwhelm the health aspects. For instance, the taking of steroids and other “performance-enhancing” substances in order to set athletic records or beat one’s competitors is counterproductive to the maintenance of good health and is often worse than doing no exercise at all. Likewise, engaging in sports such as American football, rugby, boxing, or lacrosse, which involve a high degree of physical contact and therefore a great likelihood of injury, is counterproductive to the goal of health preservation.

Supplementation, or Lack Thereof

Overall, it is important for the human body to obtain adequate quantities of essential nutrients – such as vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and fatty acids – in order for healthy function to be sustained. Because these nutrients are not automatically produced by the body in adequate amounts, they must be consumed from external sources. However, excessive amounts of many such nutrients can be toxic. Moreover, contemporary science has not discerned any regimen of extraordinary supplementation (over and above medically recommended daily values) to reliably result in longevity improvements for those who are already healthy. Worse yet, enough research exists to suggest that supplementation with vitamins and other common substances, significantly in excess of medically recommended daily values, could increase the risk of early death. Again, the evidence points to the desirability of a moderate intake of vitamins and other essential nutrients – but none of them becomes a panacea when consumed in doses significantly above the moderate ones found in foods routinely available to virtually everyone in the Western world. Mild vitamin and mineral supplements are probably not harmful and may be helpful if one’s diet indeed lacks some essential nutrients, but mega-doses of any substance should be approached with great caution.

Supplementation with drugs and hormones – absent the clear and medically determined need to treat a specific health problem – is even riskier for a healthy organism; the side effects could be great, and the benefits are dubious at present. No “magic pill” for life extension has yet been discovered, and rejuvenation therapies are decades away even if billions of dollars were poured into their research tomorrow. Even when they are necessary to treat an illness or injury, many commonly used prescription medicines can result in severe side effects, implying that they should be used with extreme caution and awareness of the risks, even when they are prescribed. The time has not yet arrived for individual self-medication with the aim of life extension. As the details of the human body’s metabolism and its effects on senescence are far from fully understood, there are no guarantees that introducing any particular substance into the immensely complex machinery of the human organism will not do more harm than good. Most people will be much safer by adopting the heuristic of not fixing that, which is not obviously broken, while avoiding harmful habits, obtaining regular medical checkups, and following the advice of evidence-based medical practitioners.

Someday, hopefully in our lifetimes, medical science might advance to the point where it might be possible to inexpensively develop a deeply personalized supplementation regimen for each individual – a more compact, precise, and targeted version of what Ray Kurzweil does today at the cost of immense time and effort. Until then, Aristotle’s golden mean is still the best heuristic to enable most of us to survive for as long as possible, which will hopefully be long enough for improvements in human knowledge and health-care delivery to usher in the era of longevity escape velocity.