“Inferno” and the Overpopulation Myth – Article by Jonathan Newman

Inferno is a great thriller, featuring Tom Hanks reprising his role as Professor Robert Langdon. The previous movie adaptations of Dan Brown’s books (Angels and Demons and The Da Vinci Code) were a success, and I expect Inferno will do well in theaters, too.

Langdon is a professor of symbology whose puzzle solving skills and knowledge of history come in high demand when a billionaire leaves a trail of clues based on Dante’s Inferno to a biological weapon that would halve the world’s population.

The villain, however, has good motives. As a radical Malthusian, he believes that the human race needs halving if it is to survive at all, even if through a plague. Malthus’s name is not mentioned in the movie, but his ideas are certainly there. Inferno provides us an opportunity to unpack this overpopulation fear, and see where it stands today.

Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) thought that the potential exponential growth of population was a problem. If population increases faster than the means of subsistence, then, “The superior power of population cannot be checked without producing misery or vice.”

Is overpopulation a problem?

The economics of population size tell a different, less scary, story. While it is certainly possible that some areas can become too crowded for some people’s preferences, as long as people are free to buy and sell land for a mutually agreeable price, overcrowding will fix itself.

As an introvert who enjoys nature and peace and quiet, I am certainly less willing to rent an apartment in the middle of a busy, crowded city. The prices I’m willing to pay for country living versus city living reflect my preferences. And, to the extent that others share my preferences or even have the opposite preferences, the use and construction of homes and apartments will be economized in both locations. Our demands and the profitability of the varied real estate offerings keep local populations in check.

But what about on a global scale? The Inferno villain was concerned with world population. He stressed the urgency of the situation, but I don’t see any reason to worry.

Google tells me that we could fit the entire world population in Texas and everybody would have a small, 100 square meter plot to themselves. Indeed, there are vast stretches of land across the globe with little to no human inhabitants. Malthus and his ideological followers must have a biased perspective, only looking at the crowded streets of a big city.

If it’s not land that’s a problem, what about the “means of subsistence”? Are we at risk of running out of food, medicine, or other resources because of our growing population?

No. A larger population not only means more mouths to feed, but also more heads, hands, and feet to do the producing. Also, as populations increase, so does the variety of skills available to make production even more efficient. More people means everybody can specialize in a more specific and more productive comparative advantage and participate in a division of labor. Perhaps this question will drive the point home: Would you rather be stranded on an island with two other people or 20 other people?

Malthus wouldn’t be a Malthusian if he could see this data

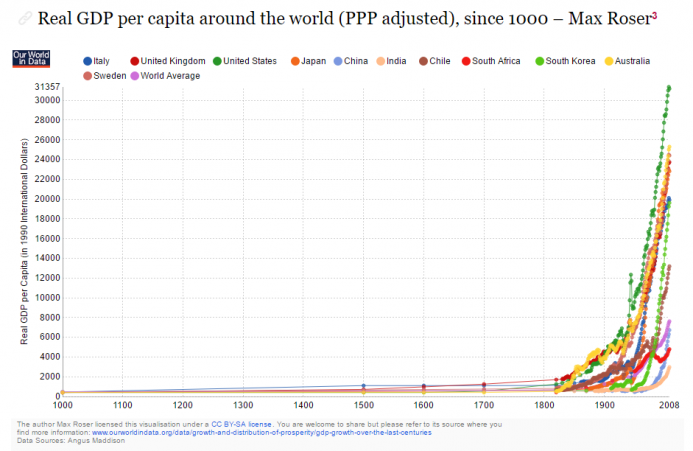

The empirical evidence is compelling, too. In the graph below, we can see the sort of world Malthus saw: one in which most people were barely surviving, especially compared to our current situation. Our 21st century world tells a different story. Extreme poverty is on the decline even while world population is increasing.

Hans Rosling, a Swedish medical doctor and “celebrity statistician,” is famous for his “Don’t Panic” message about population growth. He sees that as populations and economies grow, more have access to birth control and limit the size of their families. In this video, he shows that all countries are heading toward longer lifespans and greater standards of living.

Hans Rosling, a Swedish medical doctor and “celebrity statistician,” is famous for his “Don’t Panic” message about population growth. He sees that as populations and economies grow, more have access to birth control and limit the size of their families. In this video, he shows that all countries are heading toward longer lifespans and greater standards of living.

Finally, there’s the hockey stick of human prosperity. Estimates of GDP per capita on a global, millennial scale reveal a recent dramatic turn.

The inflection point coincides with the industrial revolution. Embracing the productivity of steam-powered capital goods and other technologies sparked a revolution in human well-being across the globe. Since then, new sources of energy have been harnessed and computers entered the scene. Now, computers across the world are connected through the internet and have been made small enough to fit in our pockets. Goods, services, and ideas zip across the globe, while human productivity increases beyond what anybody could have imagined just 50 years ago.

I don’t think Malthus himself would be a Malthusian if he could see the world today.

Jonathan Newman is a recent graduate of Auburn University and a Mises Institute Fellow. Contact: email

This article was published on Mises.org and may be freely distributed, subject to a Creative Commons Attribution United States License, which requires that credit be given to the author.