Chris Baecker

Chris Baecker

******************************

During the holidays, I took my daughters to my aunt and uncle’s house in Rogers, TX. Over the last few years, when not working their day jobs at Scott and White hospital in Temple, they have grown a large garden of marketable produce, devoting more than 4 acres to the operation. I sent some photos to a friend of mine who has his own backyard garden. His enthusiasm was palpable. This is a guy who once told me, “everyone should have a garden.”

Fast forward to this spring. I finally got around to buying a bookshelf. As I set about putting it together, I started thinking, “I could put together a nicer, sturdier one than this. All I’d need is some wood, sandpaper, stain/paint, braces … never mind. This one will do for now.”

I don’t have all the tools at my disposal to carry out that sort of a project, any more than I do for gardening. My interests lie elsewhere. In a free society like ours, each person is allowed to pursue their own preferred interests. Eventually, however, we do require other goods for sustenance, and leisure, so we trade with each other.

In what has been the most unpredictable and surprising election season of my lifetime, one issue that has come under unusually widespread attack is free trade.

The Opposition

Resistance to free trade has typically been found in the Democratic Party. Its union supporters fret about their jobs being “shipped overseas,” and environmentalists express concerns about trading with countries that lack “adequate” protections thereof. A few decades ago, that bloc was countered by the relatively more market-friendly Democratic Leadership Council, whose influence peaked with the election of Bill Clinton as president.

Remaining democratic opposition was joined by a couple of protesters from the center-right, H. Ross Perot and Patrick Buchanan. Mr. Perot famously claimed during a 1992 presidential debate that we would hear “a giant sucking sound” of manufacturing going south to Mexico. Four years later, while seeking the Republican Party nomination for President, Mr. Buchanan campaigned on a fear of losing nationality as goods and labor move more seamlessly across borders.

Nowadays, the DLC is defunct (2011) while the spirit of Messrs. Perot and Buchanan has morphed into this election season’s wild card, Donald Trump. The similarities amongst the three are many: businessmen (Perot and Trump), populist streaks, insurgent outsiders, meticulously crafted coifs, etc. They also share a skepticism of free trade.

A few Trump talking points have jumped out at me: “we don’t make things anymore,” we’re in “imbalance (deficit) with” other countries and threatening a 45% tariff on Chinese goods.

Trade protectionism has been around for ages. Our Founding Fathers supported tariffs, which used to be a prominent source of government revenue. Alexander Hamilton even coined the “infant industry” argument, whereby the government shields from international competition new and developing industries deemed important to self-sufficiency and independence.

Trade and Trump

In trade debates of modern times, Republicans have typically argued for “free” trade, whereas “fair trade” was sought by Democrats. Mr. Trump has picked up the mantle of the latter, saying the 45% tariff is merely a threat to achieve such fairness.

I’m reminded of the interrogation scene in the movie “Starsky and Hutch” where

Ben Stiller tries to coerce some information out of a suspect … by pointing the gun at his own head. Why threaten the American consumer with price hikes? Why not, for example, allow domestic steel-input consumers to benefit from rock-bottom prices that result from Chinese overproduction? How does it make sense to protect the American steel industry with a tariff of more than 500% if employment in, and value produced by, those input consumers is greater?

The answer also happens to explain why we’re lagging behind the rest of the world in the sugar trade: concentrated benefits (domestic industry) vs. dispersed costs (artificially inflated prices for consumers). Such beneficiaries typically have more clout with policymakers than consumers do. It’s this kind of rent-seeking that prevents us from being able to take advantage of the shortcomings of a centrally-planned (though certainly less so than a couple generations ago) economy like China’s, or the fact that some countries just flat out produce something more efficiently than we do.

Ironically enough, if Mr. Trump is so concerned with illegal immigration from our south, perhaps he should first take a look at the agricultural and dairy subsidies Uncle Sam doles out that put Mexican farmers out of business and drive them north to get a piece of our artificially- inflated industry.

Moreover, when he asks “(w)ho the hell cares if there’s a trade war?” someone should remind him of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of June 1930. In an effort to protect domestic agricultural and industrial interests, President Herbert Hoover signed it into law over a petition signed by a thousand economists. Other nations retaliated and the world headed toward depression. And that was when trade was a smaller part of the global economy.

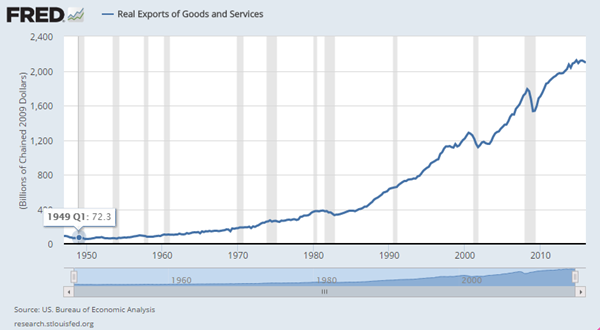

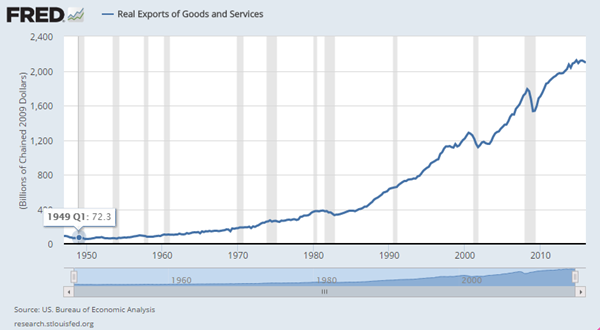

Lesson learned, after the war, the world moved toward freer trade. In that time, our real exports of goods and services rose steadily, accelerating in the mid-1980s, belying the claim that “we don’t make” stuff.

As Harvard professor and former Chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers Greg Mankiw recently pointed out in The New York Times, manufacturing is currently at an all-time high. The problem, as it were, is that we’re doing it with less manpower.

The Effectiveness of Efficiency

That very transformation is currently underway in the energy industry. Even after the price of oil started tanking, and rigs were idled, and jobs were being eliminated, production still increased. We became more efficient. It won’t take the same quantity of capital and labor to respond to $50 oil the next time it rises to that level. The displaced resources can be redeployed to other areas of the economy.

There are undoubtedly industry shakeups in freer markets. Labor, capital, and entrepreneurs are reshuffled. But our society encourages innovation by safeguarding intellectual and property rights. That allows us to find new and better ways of doing things.

This is just the latest example of our capacity to achieve the self-sufficiency that was the goal of our first Treasury Secretary (Mr. Hamilton) when he submitted to the second Congress suggestions of “encouragement” and “protection of government” in his “Reports on Manufactures.” All the “protection” we need for the aforementioned “encouragement” is between our ears. The human capital that we’ve built up over the years doesn’t go away, but rather accumulates.

Without free trade, there might be an erosion of two of its most important exports: peace and freedom. The world has to cooperate and get along if we all want to prosper. And the freer the people, the greater the likelihood of greater prosperity. Besides, should that peace unfortunately break down again someday, the Second Amendment and our bread basket give us time to dust off and tap that know-how to rev up the necessary industries.

Counterbalancing Deficits

Nevertheless, more trade liberalization is afoot. My industry has a new market: the rest of the world, thanks to the repeal of the oil export ban last December. That’ll surely alleviate something else nearly all our leaders are prone to complain about: our trade deficit.

It’s a curious thing that you rarely hear that it’s actually only half of an equation, but it is.

The balance of payments (BoP) is basically an accounting of our international transactions. The current account (trade) is the one we always hear about when it’s in deficit. Interestingly enough, it tends to trend back toward break-even only when we’re heading toward recession. It makes sense that imports rise in good times. “We’re Americans,” I tell my students, “we like to buy stuff. We like to buy stuff so much, we rent storage facilities in which to put all our extra stuff!” Regardless, there’s nothing inherently wrong with a trade deficit.

The counterbalance is the capital account. We have a big example of that in our backyard: the Toyota plant in south San Antonio. This is foreign direct investment. That plant is in the heart of truck country. It gives Toyota direct access to that market here. And, they employ highly-skilled Texans. That seems like a win-win, a sign of strength perhaps, when a foreign company wants to locate operations here.

You actually contribute to the capital account when you crack open a Bud Light after feeding Purina to Scooby, who was hungry because you forgot to feed him while you were eating a Smithfield ham steak (that had been stored in a GE freezer) for dinner before going to see “X-Men: Apocalypse” at the AMC Rivercenter 11. All those companies are foreign-owned. The profit portion of the prices paid for those goods is exported to another country. Foreign entities saw value in the brand recognition of items Americans know and love. And they were able to buy those companies in part because they do more of something that we don’t: save.

When the consumer expenditure portion of the Gross Domestic Product [GDP] started climbing in the 1980s from 60% to almost 70% today, it was arguably fueled by the concurrent proliferation of the all-purpose credit card. Perhaps it goes without saying, but when you’re spending, you’re not saving. And when you’re borrowing, you are dissaving. Much of the consumer savings derived from more efficient global production of goods could go to more savings. Instead, it seems to go toward buying more stuff.

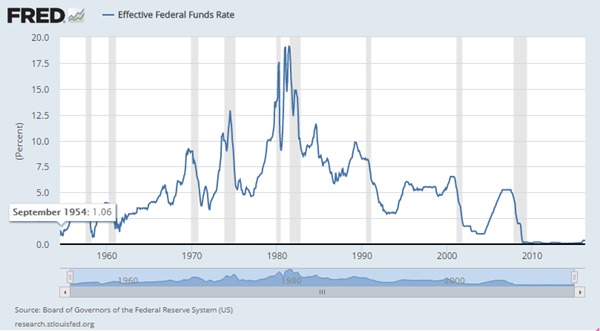

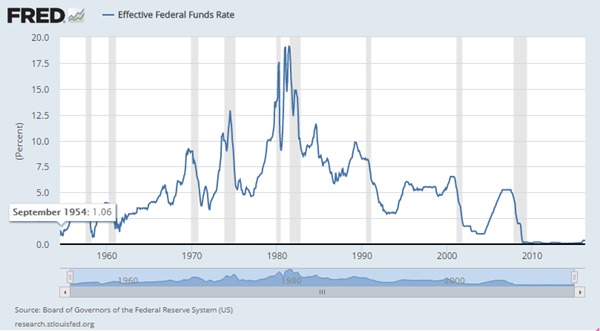

When you think about it though, our incentive to save has slid right alongside available interest rates.

A couple years after they were pushed way up to break the inflation of the 1970s, interest rates have been on a steady march downward: ~7-8% in 1980s, ~5% in the 1990s, half that in the 2000s, and now near 0%. Monetary policy that could be enticing us to invest in learning new skills, opening a new business, guarding against unforeseen events, etc., instead has nudged us toward $1,000,000,000,000 in both credit card and automobile debt this year. What was the current trade deficit again?

If bringing down the trade deficit is the goal, increasing domestic savings and investment is preferable to erecting trade barriers. And if curbing interest-bearing consumer indebtedness happens as well, all the better.

While former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton seems like little more than a 21st century version of the pandering, “meaningless platitude-spouting” Kevin Fogerty from a classic episode of “Cheers,” Senator Bernie Sanders and Mr. Trump have been more consistent in their views toward free trade. But the aggressive tone they sometimes take toward it and our trading partners reminds me of when my four daughters (average age, 9) bicker with one another. Only it’s more understandable that my girls have to be taught to take the high road.

As for me, one of these days I could take up woodworking, or gardening, or some other hobby/trade that produces tangible output. Right now though, my spare time is best served educating. It’s what I like to do. It’s where I feel most productive. And given this season’s crop of presidential aspirants, there seems to be a need for it.

Christopher E. Baecker manages fixed assets for Pioneer Energy Services and is an adjunct lecturer of economics at Northwest Vista College in San Antonio. He can be reached via www.chrisbaecker.com, @chrisbaecker71 & LinkedIn.com

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.