In other words these are the real salient and significant problems needing to be addressed by Transhumanist and Technoprogressive communities. The good news is that the ones making the most progress in terms of deliberating the possible repercussions of emerging technologies are Transhumanist and Technoprogressive communities. The large majority of thinkers and theoreticians working on Existential Risk and Global Catastrophic Risk, like The Future of Humanity Institute and the Lifeboat Foundation, share Technoprogressive inclinations. Meanwhile, the largest proponents of the need to ensure wide availability of enhancement technologies, as well as the need for provision of personhood rights to non-biologically-substrated persons, are found amidst the ranks of Technoprogressive Think Tanks like the IEET.

Simply look around you. An idiosyncratic genus of great ape did this! Consider how remarkably absurd it would seem for the gorilla genus to have coordinated their efforts to build skyscrapers; to engineer devices that took them to the Moon; to be able to send a warning or mating call to the other side of the earth in less time than such a call could actually be made via physical vocal cords. We live in a world of artificial wonder, and act as though it were the most mundane thing in the world. But considered in terms of geological time, the unprecedented feat of culture and artificial artifact just happened. We are still in the fledging infancy of the future, which only began when we began making it ourselves.

We have no reason whatsoever to doubt the eventual technological feasibility of anything, really, when we consider all the things that were said to be impossible yet happened, all the things that were said to be possible and did happen, and all the things that were unforeseen completely yet happened nonetheless. In light of history, it seems more likely than a given thing would eventually be possible via technology than that it wouldn’t ever be possible. I fully appreciate the grandeur of this claim – but I stand by it nonetheless. To claim that a given ability will probably not be eventually possible to implement via technology is to laugh in the face of history to some extent.

The main exceptions to this claim are abilities wherein you limit or specify the route of implementation. Thus it probably would not be eventually possible to, say, infer the states of all the atoms comprising the Eifel Tower from the state of a single atom in your fingernail: categories of ability where you specify the implementation as the end-ability – as in the case above, the end ability was to infer the state of all the atoms in the Eifel Tower from the state of a single atom.

These exceptions also serve to illustrate the paramount feature allowing technology to possiblize the seemingly improbable: novel means of implementation. Very often there is a bottleneck in the current system we use to accomplish something that limits the scope of tis abilities and prevents certain objectives from being facilitated by it. In such cases a whole new paradigm of approach is what moves progress forward to realizing that objective. If the goal is the reversal and indefinite remediation of the causes and sources of aging, the paradigms of medicine available at the turn of the 20th century would have seemed to be unable to accomplish such a feat.

The new paradigm of biotechnology and genetic engineering was needed to formulate a scientifically plausible route to the reversal of aging-correlated molecular damage – a paradigm somewhat non-inherent in the medical paradigms and practices common at the turn of the 20th Century. It is the notion of a new route to implementation, a wholly novel way of making the changes that could lead to a given desired objective, that constitutes the real ability-actualizing capacity of technology – and one that such cases of specified implementation fail to take account of.

One might think that there are other clear exceptions to this as well: devices or abilities that contradict the laws of physics as we currently understand them – e.g., perpetual-motion machines. Yet even here we see many historical antecedents exemplifying our short-sighted foresight in regard to “the laws of physics”. Our understanding of the physical “laws” of the universe undergo massive upheaval from generation to generation. Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions challenged the predominant view that scientific progress occurred by accumulated development and discovery when he argued that scientific progress is instead driven by the rise of new conceptual paradigms categorically dissimilar to those that preceded it (Kuhn, 1962), and which then define the new predominant directions in research, development, and discovery in almost all areas of scientific discovery and conceptualization.

Kuhn’s insight can be seen to be paralleled by the recent rise in popularity of Singularitarianism, which today seems to have lost its strict association with I.J. Good‘s posited type of intelligence explosion created via recursively self-modifying strong AI, and now seems to encompass any vision of a profound transformation of humanity or society through technological growth, and the introduction of truly disruptive emerging and converging (e.g., NBIC) technologies.

This epistemic paradigm holds that the future is less determined by the smooth progression of existing trends and more by the massive impact of specific technologies and occurrences – the revolution of innovation. Kurzweil’s own version of Singularitarianism (Kurzweil, 2005) uses the systemic progression of trends in order to predict a state of affairs created by the convergence of such trends, wherein the predictable progression of trends points to their own destruction in a sense, as the trends culminate in our inability to predict past that point. We can predict that there are factors that will significantly impede our predictive ability thereafter. Kurzweil’s and Kuhn’s thinking are also paralleled by Buckminster Fuller in his notion of ephemeralization (i.e., doing more with less), the post-industrial information economies and socioeconomic paradigms described by Alvin Toffler (Toffler, 1970), John Naisbitt (Naisbitt 1982), and Daniel Bell (Bell, 1973), among others.

It can also partly be seen to be inherent in almost all formulations of technological determinism, especially variants of what I call reciprocal technological determinism (not simply that technology determines or largely constitutes the determining factors of societal states of affairs, not simply that tech affects culture, but rather than culture affects technology which then affects culture which then affects technology) a là Marshall McLuhan (McLuhan, 1964) . This broad epistemic paradigm, wherein the state of progress is more determined by small but radically disruptive changes, innovation, and deviations rather than the continuation or convergence of smooth and slow-changing trends, can be seen to be inherent in variants of technological determinism because technology is ipso facto (or by its very defining attributes) categorically new and paradigmically disruptive, and if culture is affected significantly by technology, then it is also affected by punctuated instances of unintended radical innovation untended by trends.

That being said, as Kurzweil has noted, a given technological paradigm “grows out of” the paradigm preceding it, and so the extents and conditions of a given paradigm will to some extent determine the conditions and allowances of the next paradigm. But that is not to say that they are predictable; they may be inherent while still remaining non-apparent. After all, the increasing trend of mechanical components’ increasing miniaturization could be seen hundreds of years ago (e.g., Babbage knew that the mechanical precision available via the manufacturing paradigms of his time would impede his ability in realizing his Baggage Engine, but that its implementation would one day be possible by the trend of increasingly precise manufacturing standards), but the fact that it could continue to culminate in the ephemeralization of Bucky Fuller (Fuller, 1976) or the mechanosynthesis of K. Eric Drexler (Drexler, 1986).

Moreover, the types of occurrence allowed by a given scientific or methodological paradigm seem at least intuitively to expand, rather than contract, as we move forward through history. This can be seen lucidly in the rise of Quantum Physics in the early 20th Century, which delivered such conceptual affronts to our intuitive notions of the possible as non-locality (i.e., quantum entanglement – and with it quantum information teleportation and even quantum energy teleportation, or in other words faster-than-light causal correlation between spatially separated physical entities), Einstein’s theory of relativity (which implied such counter-intuitive notions as measurement of quantities being relative to the velocity of the observer, e.g., the passing of time as measured by clocks will be different in space than on earth), and the hidden-variable theory of David Bohm (which implied such notions as the velocity of any one particle being determined by the configuration of the entire universe). These notions belligerently contradict what we feel intuitively to be possible. Here we have claims that such strange abilities as informational and energetic teleportation, faster-than-light causality (or at least faster-than-light correlation of physical and/or informational states) and spacetime dilation are natural, non-technological properties and abilities of the physical universe.

Technology is Man’s foremost mediator of change; it is by and large through the use of technology that we expand the parameters of the possible. This is why the fact that these seemingly fantastic feats were claimed to be possible “naturally”, without technological implementation or mediation, is so significant. The notion that they are possible without technology makes them all the more fantastical and intuitively improbable.

We also sometimes forget the even more fantastic claims of what can be done through the use of technology, such as stellar engineering and mega-scale engineering, made by some of big names in science. There is the Dyson Sphere of Freeman Dyson, which details a technological method of harnessing potentially the entire energetic output of a star (Dyson, 1960). One can also find speculation made by Dyson concerning the ability for “life and communication [to] continue for ever, using a finite store of energy” in an open universe by utilizing smaller and smaller amounts of energy to power slower and slower computationally emulated instances of thought (Dyson, 1979).

There is the Tipler Cylinder (also called the Tipler Time Machine) of Frank J. Tipler, which described a dense cylinder of infinite length rotating about its longitudinal axis to create closed timelike curves (Tipler, 1974). While Tipler speculated that a cylinder of finite length could produce the same effect if rotated fast enough, he didn’t provide a mathematical solution for this second claim. There is also speculation by Tipler on the ability to utilize energy harnessed from gravitational shear created by the forced collapse of the universe at different rates and different directions, which he argues would allow the universe’s computational capacity to diverge to infinity, essentially providing computationally emulated humans and civilizations the ability to run for an infinite duration of subjective time (Tipler, 1986, 1997).

We see such feats of technological grandeur paralleled by Kurt Gödel, who produced an exact solution to the Einstein field equations that describes a cosmological model of a rotating universe (Gödel, 1949). While cosmological evidence (e.g., suggesting that our universe is not a rotating one) indicates that his solution doesn’t describe the universe we live in, it nonetheless constitutes a hypothetically possible cosmology in which time-travel (again, via a closed timelike curve) is possible. And because closed timelike curves seem to require large amounts of acceleration – i.e. amounts not attainable without the use of technology – Gödel’s case constitutes a hypothetical cosmological model allowing for technological time-travel (which might be non-obvious, since Gödel’s case doesn’t involve such technological feats as a rotating cylinder of infinite length, rather being a result derived from specific physical and cosmological – i.e., non-technological – constants and properties).

These are large claims made by large names in science (i.e., people who do not make claims frivolously, and in most cases require quantitative indications of their possibility, often in the form of mathematical solutions, as in the cases mentioned above) and all of which are made possible solely through the use of technology. Such technological feats as the computational emulation of the human nervous system and the technological eradication of involuntary death pale in comparison to the sheer grandeur of the claims and conceptualizations outlined above.

We live in a very strange universe, which is easy to forget midst our feigned mundanity. We have no excuse to express incredulity at Transhumanist and Technoprogressive conceptualizations considering how stoically we accept such notions as the existence of sentient matter (i.e., biological intelligence) or the ability of a genus of great ape to stand on extraterrestrial land.

Thus, one of the most common counter-arguments launched at many Transhumanist and Technoprogressive claims and conceptualizations – namely, technical infeasibility based upon nothing more than incredulity and/or the lack of a definitive historical precedent – is one of the most baseless counter-arguments as well. It would be far more credible to argue for the technical infeasibility of a given endeavor within a certain time-frame. Not only do we have little, if any, indication that a given ability or endeavor will fail to eventually become realizable via technology given enough development-time, but we even have historical indication of the very antithesis of this claim, in the form of the many, many instances in which a given endeavor or feat was said to be impossible, only to be realized via technological mediation thereafter.

It is high time we accepted the fallibility of base incredulity and the infeasibility of the technical-infeasibility argument. I remain stoically incredulous at the audacity of fundamental incredulity, for nothing should be incredulous to man, who makes his own credibility in any case, and who is most at home in the necessary superfluous.

Franco Cortese is an editor for Transhumanity.net, as well as one of its most frequent contributors. He has also published articles and essays on Immortal Life and The Rational Argumentator. He contributed 4 essays and 7 debate responses to the digital anthology Human Destiny is to Eliminate Death: Essays, Rants and Arguments About Immortality.

References

Bell, D. (1973). “The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting, Daniel Bell.” New York: Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-01281-7.

Dyson, F. (1960) “Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation”. Science 131: 1667-1668.

Dyson, F. (1979). “Time without end: Physics and biology in an open universe,” Reviews of Modern Physics 51 (3): 447-460.

Fuller, R.B. (1938). “Nine Chains to the Moon.” Anchor Books pp. 252–59.

Gödel, K. (1949). “An example of a new type of cosmological solution of Einstein’s field equations of gravitation”. Rev. Mod. Phys. 21 (3): 447–450.

Kuhn, Thomas S. (1962). “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1st ed.).” University of Chicago Press. LCCN 62019621.

Kurzweil, R. (2005). “The Singularity is Near.” Penguin Books.

Mcluhan, M. (1964). “Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man”. 1st Ed. McGraw Hill, NY.

Niasbitt, J. (1982). “Megatrends.” Ten New Directions Transforming Our Lives. Warner Books.

Tipler, F. (1974) “Rotating Cylinders and Global Causality Violation”. Physical Review D9, 2203-2206.

Tipler, F. (1986). “Cosmological Limits on Computation”, International Journal of Theoretical Physics 25 (6): 617-661.

Tipler, F. (1997). The Physics of Immortality: Modern Cosmology, God and the Resurrection of the Dead. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-46798-2.

Toffler, A. (1970). “Future shock.” New York: Random House.

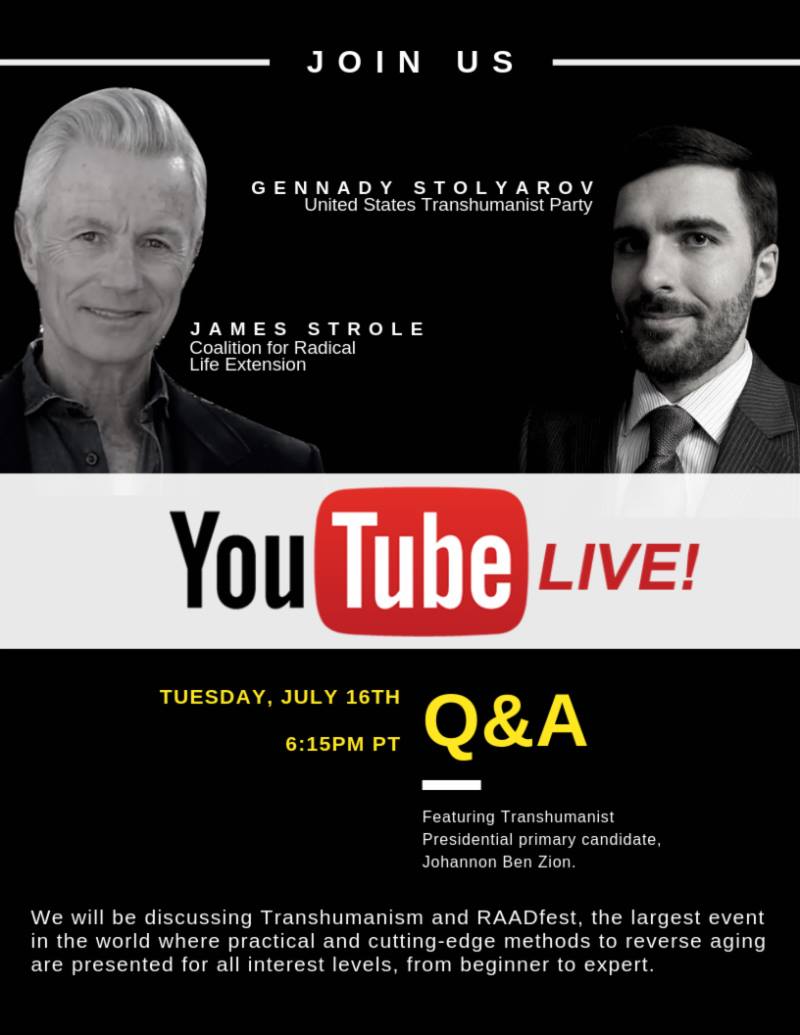

James Strole

James Strole