While the achievement of radical human life extension is primarily a scientific and technical challenge, the political environment in which research takes place is extremely influential as to the rate of progress, as well as whether the research could even occur in the first place, and whether consumers could benefit from the fruits of such research in a sufficiently short timeframe. I, as a libertarian, do not see massive government funding of indefinite life extension as the solution – because of the numerous strings attached and the possibility of such funding distorting and even stalling the course of life-extension research by rendering it subject to pressures by anti-longevity special-interest constituencies. (I can allow an exception for increased government medical spending if it comes at the cost of major reductions in military spending; see my item 6 below for more details.) Rather, my proposed solutions focus on liberating the market, competition, and consumer choice to achieve an unprecedented rapidity of progress in life-extension treatments. This is the fastest and most reliable way to ensure that people living today will benefit from these treatments and will not be among the last generations to perish. Here, I describe six major types of libertarian reforms that could greatly accelerate progress toward indefinite human life extension.

1. Repeal of the requirement for drugs and medical treatments to obtain FDA approval before being used on willing patients. The greatest threat to research on indefinite life extension – and the availability of life-extending treatments to patients – is the current requirement in the United States (and analogous requirements elsewhere in the Western world) that drugs or treatments may not be used, even on willing patients, unless approval for such drugs or treatments is received from the Food and Drug Administration (or an analogous national regulatory organization in other countries). This is a profound violation of patient sovereignty; a person who is terminally ill is unable to choose to take a risk on an unapproved drug or treatment unless this person is fortunate enough to participate in a clinical trial. Even then, once the clinical trial ends, the treatment must be discontinued, even if it was actually successful at prolonging the person’s life. This is not only profoundly tragic, but morally unconscionable as well.

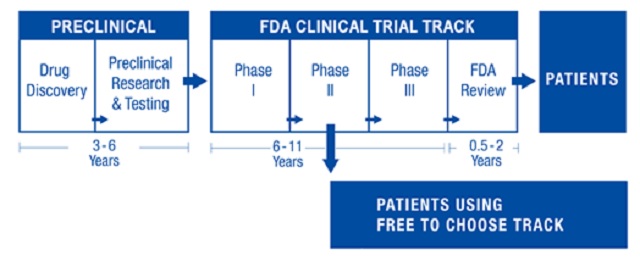

As a libertarian, I would prefer to see the FDA abolished altogether and for competing private certification agencies to take its place. But even this transformation does not need to occur in order for the worst current effects of the FDA to be greatly alleviated. The most critical reform needed is to allow unapproved drugs and treatments to be marketed and consumed. If the FDA wishes to strongly differentiate between approved and unapproved treatments, then a strongly worded warning label could be required for unapproved treatments, and patients could even be required to sign a consent form stating that they have been informed of the risks of an unapproved treatment. While this is not a perfect libertarian solution, it is a vast incremental improvement over the status quo, in that hundreds of thousands of people who would die otherwise would at least be able to take several more chances at extending their lives – and some of these attempts will succeed, even if they are pure gambles from the patient’s point of view. Thus, this reform to directly extend many lives and to redress a moral travesty should be the top political priority of advocates of indefinite life extension. Over the coming decades, its effect will be to allow cutting-edge treatments to reach a market sooner and thus to enable data about those treatments’ effects to be gathered more quickly and reliably. Because many treatments take 10-15 years to receive FDA approval, this reform could by itself speed up the real-world advent of indefinite life extension by over a decade.

2. Abolishing medical licensing protectionism. The current system for licensing doctors is highly monopolistic and protectionist – the result of efforts by the American Medical Association in the early 20th century to limit entry into the profession in order to artificially boost incomes for its members. The medical system suffers today from too few doctors and thus vastly inflated patient costs and unacceptable waiting times for appointments. Instead of prohibiting the practice of medicine by all except a select few who have completed an extremely rigorous and cost-prohibitive formal medical schooling, governments in the Western world should allow the market to determine different tiers of medical care for which competing private certifications would emerge. For the most specialized and intricate tasks, high standards of certification would continue to exist, and a practitioner’s credentials and reputation would remain absolutely essential to convincing consumers to put their lives in that practitioner’s hands. But, with regard to routine medical care (e.g., annual check-ups, vaccinations, basic wound treatment), it is not necessary to receive attention from a person with a full-fledged medical degree. Furthermore, competition among certification providers would increase quality of training and lower its price, as well as accelerate the time needed to complete the training. Such a system would allow many more young medical professionals to practice without undertaking enormous debt or serving for years (if not decades) in roles that offer very little remuneration while entailing a great deal of subservience to the hierarchy of some established institution or another. Ultimately, without sufficient doctors to affordably deliver life-extending treatments when they become available, it would not be feasible to extend these treatments to the majority of people. Would there be medical quacks under such a system of privatized certification? There are always quacks, including in the West today – and no regulatory system can prevent those quacks from exploiting willing dupes. But full consumer choice, combined with the strong reputational signals sent by the market, would ensure that the quacks would have a niche audience only and would never predominate over scientifically minded practitioners.

3. Abolishing medical patent monopolies. Medical patents – in essence, legal grants of monopoly for limited periods of time – greatly inflate the cost of drugs and other treatments. Especially in today’s world of rapidly advancing biotechnology, a patent term of 20 years essentially means that no party other than the patent holder (or someone paying royalties to the patent holder) may innovate upon the patented medicine for a generation, all while the technological potential for such innovation becomes glaringly obvious. As much innovation consists of incremental improvements on what already exists, the lack of an ability to create derivative drugs and treatments that tweak current approaches implies that the entire medical field is, for some time, stuck at the first stages of a treatment’s evolution – with all of the expense and unreliability this entails. More appallingly, many pharmaceutical companies today attempt to re-patent drugs that have already entered the public domain, simply because the drugs have been discovered to have effects on a disease different from the one for which they were originally patented. The result of this is that the price of the re-patented drug often spikes by orders of magnitude compared to the price level during the period the drug was subject to competition. Only a vibrant and competitive market, where numerous medical providers can experiment with how to improve particular treatments or create new ones, can allow for the rate of progress needed for the people alive today to benefit from radical life extension. Some may challenge this recommendation with the argument that the monopoly revenues from medical patents are necessary to recoup the sometimes enormous costs that pharmaceutical companies incur in researching and testing the drug and obtaining approval from regulatory agencies such as the FDA. But if the absolute requirement of FDA approval is removed as I recommend, then these costs will plummet dramatically, and drug developers will be able to realize revenues much more quickly than in the status quo. Furthermore, the original developer of an innovation will still always benefit from a first-mover advantage, as it takes time for competitors to catch on. If the original developer can maintain high-quality service and demonstrate the ability to sell a safe product, then the brand-name advantage alone can secure a consistent revenue stream without the need for a patent monopoly.

4. Abolishing software patent monopolies. With the rapid growth of computing power and the Internet, much more medical research is becoming dependent on computation. In some fields such as genome sequencing, the price per computation is declining at a rate even far exceeding that of Moore’s Law. At the same time, ordinary individuals have an unprecedented opportunity to participate in medical research by donating their computer time to distributed computing projects. Software, however, remains artificially scarce because of patent monopolies that have increasingly been utilized by established companies to crush innovation (witness the massively expensive and wasteful patent wars over smartphone and tablet technology). Because most software is not cost-prohibitive even today, the most pernicious effect of software patents is not on price, but on the existence of innovation per se. Because there exist tens of thousands of software patents (many held defensively and not actually utilized to market anything), any inventor of a program that assists in medical, biotechnological, or nanotechnological computations must proceed with extreme caution, lest he run afoul of some obscure patent that is held for the specific purpose of suing people like him out of existence once his product is made known. The predatory nature of the patent litigation system serves to deter many potential innovators from even trying, resulting in numerous foregone discoveries that could further accelerate the rate at which computation could facilitate medical progress. Ideally, all software patents (and all patents generally) should be abolished, and free-market competition should be allowed to reign. But even under a patent system, massive incremental improvements could be made. First, non-commercial uses of a patent should be rendered immune to liability. This would open up a lot of ground for non-profit medical research using distributed computing. Second, for commercial use of patents, a system of legislatively fixed maximum royalties could emerge – where the patent holder would be obligated to allow a competitor to use a particular patented product, provided that a certain price is paid to the patent holder – and litigation would be permanently barred. This approach would continue to give a revenue stream to patent holders while ensuring that the existence of a patent does not prevent a product from coming to market or result in highly uncertain and variable litigation costs.

5. Reestablishing the two-party doctor-patient relationship. The most reliable and effective medical care occurs when the person receiving it has full discretion over the level of treatment to be pursued, while the person delivering it has full discretion over the execution (subject to the wishes of the consumer). When a third party – whether private or governmental – pays the bills, it also assumes the position of being able to dictate the treatment and limit patient choice. Third-party payment systems do not preclude medical progress altogether, but they do limit and distort it in significant ways. They also result in the “rationing” of medical care based on the third party’s resources, rather than those of the patient. Perversely enough, third-party payment systems also discourage charity on the part of doctors. For instance, Medicare in the United States prohibits doctors who accept its reimbursements from treating patients free of charge. Mandates to utilize private health insurance in the United States and governmental health “insurance” elsewhere in the Western world have had the effect of forcing patients to be restricted by powerful third parties in this way. While private third-party payment systems should not be prohibited, all political incentives for third-party medical payment systems should be repealed. In the United States, the pernicious health-insurance mandate of the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare) should be abolished, as should all requirements and political incentives for employers to provide health insurance. Health insurance should become a product whose purchase is purely discretionary on a free market. This reform would have many beneficial effects. First, by decoupling insurance from employment, it would ensure that those who do rely on third-party payments for medical care will not have those payments discontinued simply because they lose their jobs. Second, insurance companies would be encouraged to become more consumer-friendly, since they will need to deal with consumers directly, rather than enticing employers – whose interests in an insurance product may be different from those of their employees. Third, insurance companies would be entirely subject to market forces – including the most powerful consumer protection imaginable: the right of a consumer to exit from a market entirely. Fourth and most importantly, the cost of medical care would decline dramatically, since it would become subject to direct negotiation between doctors and patients, while doctors would be subject to far less of the costly administrative bureaucracy associated with managing third-party payments.

In countries where government is the third-party payer, the most important reform is to render participation in the government system voluntary. The worst systems of government healthcare are those where private alternatives are prohibited, and such private competition should be permitted immediately, with no strings attached. Better yet, patients should be permitted to opt out of the government systems altogether by being allowed to save on their taxes if they renounce the benefits from such systems and opt for a competing private system instead. Over time, the government systems would shrink to basic “safety nets” for the poorest and least able, while standards of living and medical care would rise to the level that ever fewer people would find themselves in need of such “safety nets”. Eventually, with a sufficiently high level of prosperity and technological advancement, the government healthcare systems could be phased out altogether without adverse health consequences to anyone.

6. Replacement of military spending with medical research. While, as a libertarian, I do not consider medical research to be the proper province of government, there are many worse ways for a government to spend its money – for instance, by actively killing people in wasteful, expensive, and immoral wars. If government funds are spent on saving and extending lives rather than destroying them, this would surely be an improvement. Thus, while I do not support increasing aggregate government spending to fund indefinite life extension (or medical research generally), I would advocate a spending-reduction plan where vast amounts of military spending are eliminated and some fraction of such spending is replaced with spending on medical research. Ideally, this research should be as free from “strings attached” as possible and could be funded through outright unconditional grants to organizations working on indefinite life extension. However, in practice it is virtually impossible to avoid elements of politicization and conditionality in government medical funding. Therefore, this plan should be implemented with the utmost caution. Its effectiveness could be improved by the passage of legislation to expressly prohibit the government from dictating the methods, outcomes, or applications of the research it funds, as well as to prohibit non-researchers from acting as lobbyists for medical research. An alternative to this plan could be to simply lower taxes across the board by the amount of reduction in military spending. This would have the effect of returning wealth to the general public, some of which would be spent on medical research, while another portion of these returned funds would increase consumers’ bargaining power in the medical system, resulting in improved treatments and more patient sovereignty.