Antoninus Pius: The Greatest Roman Emperor You’ve Never Heard Of – Article by Marc Hyden

*************************

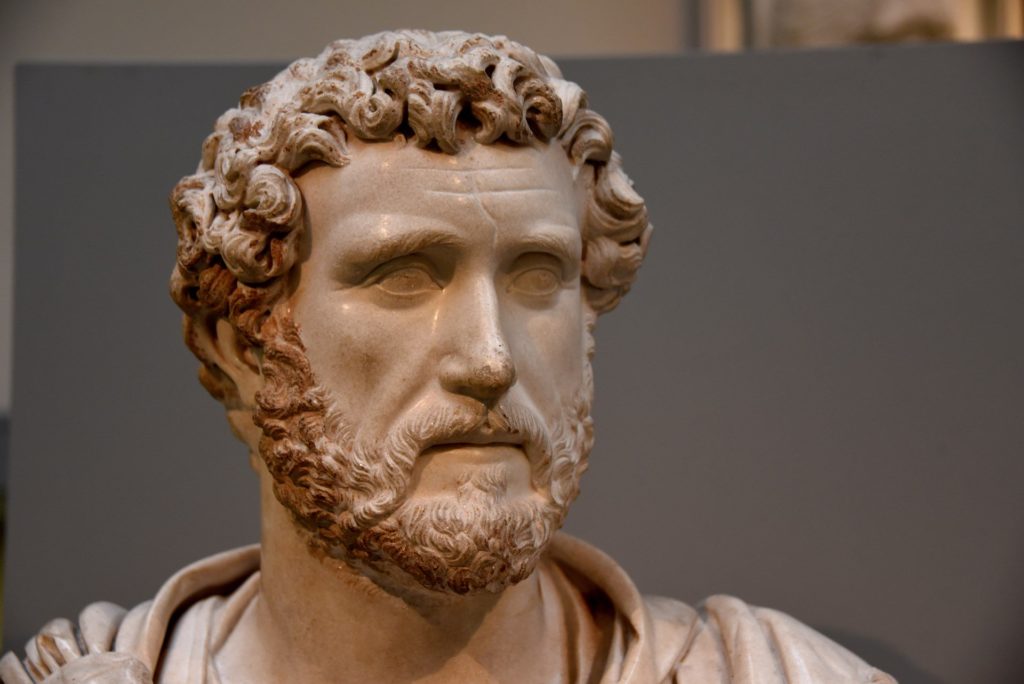

Photograph by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg)

[CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

In the book of Genesis, God agreed not to destroy Sodom if Abraham could find 10 righteous people there. Abraham failed, and God wiped the city from the face of the earth.

More recently (and much less importantly), my friend and former Foundation for Economic Education president Larry Reed issued a similar challenge: He asked me to identify one good Roman emperor—besides Marcus Aurelius. I immediately felt a bit like Abraham, frantically searching for a needle in a haystack. Thankfully, Larry didn’t threaten to destroy Rome if my quest failed.

Roman Emperors

But it was a difficult endeavor nonetheless because most Roman emperors, at least at certain points in their lives, were little more than murderous megalomaniacs too willing to spark wars for their own benefit and chip away at the Romans’ liberties. This is true even for the most revered emperors, including Augustus, Hadrian, and Constantine.

After accepting Larry’s challenge and ruminating over it, one emperor finally came to mind: Antoninus Pius. While imperfect, for the most part, Antoninus ruled with prudence, restraint, and moderation. He is known as one of the so-called “five good emperors,” but his name has survived in relative obscurity because history is often kinder to ambitious conquerors and great builders than to those who respect liberty and govern with a servant’s heart.

Antoninus understood that if he governed justly, the emperorship would be a major sacrifice, not a windfall

Born in 86 AD, Antoninus came from an influential, wealthy family. Early in his life, he enjoyed a successful career as a public administrator. But when then-Emperor Hadrian’s health began to fail, he named Antoninus his heir even though Antoninus may not have wanted the honor. In fact, Hadrian purportedly acknowledged that Antoninus was “far from desiring any such power” but nevertheless believed he would “accept the office even against his will.”

Not long after, Hadrian died, and Antoninus became emperor. When Antoninus assumed office, he told his wife, “Now that we have gained an empire, we have lost even what we had before.” These words show Antoninus understood that if he governed justly, the emperorship would be a major sacrifice, not a windfall.

Antoninus’ Rule

Antoninus proved to be a forgiving and scrupulous ruler. One of his first acts as emperor was to annul some of Hadrian’s final decrees. The ailing Roman had condemned an untold number of senators, but Antoninus opted for mercy and freed the men. According to some historians, this is why the Senate bestowed the appellation of “Pius” on Antoninus. But the new emperor didn’t simply spare other people’s enemies. When a conspiracy formed against him, the Senate, not Antoninus, prosecuted the attempted usurper, but Antoninus prohibited the rebel’s co-conspirators from being investigated. Beyond these acts of mercy, Antoninus also abolished the employment of informers and announced that no senator would be executed during his reign.

While he accepted some honors, including the cognomen of Pius, he rejected others. For instance, the Senate and the Roman people so adored Antoninus that they offered to rename the month of September after him, but he flatly refused the honor. Indeed, Antoninus often seemed to eschew the grandeur of his office. He sold off imperial lands, reduced or eliminated superfluous salaries, and lived in his own villas rather than imperial estates. He never even traveled beyond Campania during the course of his reign because he believed he simply could not justify draining the public treasury for travel.

While several conflicts erupted during his long reign, many were defensive in nature. Antoninus didn’t seek to massively increase Rome’s domain.

Antoninus was frugal in other ways, too. He conscientiously guarded the public treasury while simultaneously reducing confiscations and his subjects’ tax burden. On more than one occasion, he chose to expend personal resources to support the empire. For example, he contributed money to repair Hadrian’s construction projects and, during a famine, he provided free wine, oil, and wheat to the Romans at his own expense. He so prudently managed the state’s finances that when he died, he left the public treasury with a massive surplus—a rarity in old Rome.

Part of this surplus appears to be related to Antoninus’ aversion to vanity projects and unnecessary wars. Like many emperors, he was a builder, though not nearly to the degree of others, and his construction projects do not seem to have been designed to glorify himself—at least not overtly. And while several conflicts erupted during his long reign, many were defensive in nature. What’s more, Antoninus didn’t seek to massively increase Rome’s domain. Only two small advances occurred during his tenure, in Britannia and Germania, but it appears that his rationale may have been, at least in part, to adjust the borders so that the Romans could more economically defend the frontier.

A Virtuous Emperor

Unlike many of his predecessors and successors, Antoninus seemed to legitimately care for his subjects and the state. He established an endowment to support poverty-stricken, orphaned girls; he loaned personal money at a four percent interest rate (a low rate at the time) to those in need; he didn’t initiate any Christian persecutions, and he sought to return prestige and respect to the Senate. In fact, his only major blunder was that he debased the silver Roman denarius by around five percent in order to fund a major celebration.

Aside from this misstep, volumes could be written about Antoninus’ virtues. His life is perhaps best summed up by his successor, Marcus Aurelius, who described Antoninus as a grounded, introspective, and humble man who was respectful of others’ liberties. Aurelius wrote, “Though all his actions were guided by a respect for constitutional precedent, he would never go out of his way to court public recognition of this.”

Antonius’ biographer, Julius Capitolinus, likewise glowingly recorded:

Almost alone of all emperors [Antoninus] lived entirely unstained by the blood of either citizen or foe so far as was in his power.

Marc Hyden is a conservative political activist and an amateur Roman historian.

This article was originally published by the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE).