Paul Driessen

September 9, 2013

******************************

Activist groups continue to promote scary stories that honeybees are rapidly disappearing, dying off at “mysteriously high rates,” potentially affecting one-third of our food crops and causing global food shortages. Time Magazine says readers need to contemplate “a world without bees,” while other “mainstream media” articles have sported similar headlines.

The Pesticide Action Network and NRDC are leading campaigns that claim insecticides, especially neonicotinoids, are at least “one of the key factors,” if not the principle or sole reason for bee die-offs.

Thankfully, the facts tell a different story – two stories, actually. First, most bee populations and most managed hives are doing fine, despite periodic mass mortalities that date back over a thousand years. Second, where significant depopulations have occurred, many suspects have been identified, but none has yet been proven guilty, although researchers are closing in on several of them.

Major bee die-offs have been reported as far back as 950, 992 and 1443 AD in Ireland. 1869 brought the first recorded case of what we now call “colony collapse disorder,” in which hives full of honey are suddenly abandoned by their bees. More cases of CCD or “disappearing disease” have been reported in recent decades, and a study by bee researchers Robyn Underwood and Dennis vanEngelsdorp chronicles more than 25 significant bee die-offs between 1868 and 2003. However, contrary to activist campaigns and various news stories, both wild and managed bee populations are stable or growing worldwide.

Beekeeper-managed honeybees, of course, merit the most attention, since they pollinate many important food crops, including almonds, fruits and vegetables. (Wheat, rice and corn, on the other hand, do not depend at all on animal pollination.) The number of managed honeybee hives has increased some 45% globally since 1961, Marcelo Aizen and Lawrence Harder reported in Current Biology – even though pesticide overuse has decimated China’s bee populations.

Even in Western Europe, bee populations are gradually but steadily increasing. The trends are similar in other regions around the world, and much of the decline in overall European bee populations is due to a massive drop in managed honeybee hives in Eastern Europe, after subsidies ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union. In fact, since neonicotinoid pesticides began enjoying widespread use in the 1990s, overall bee declines appear to be leveling off or have even diminished.

Nevertheless, in response to pressure campaigns, the EU banned neonics – an action that could well make matters worse, as farmers will be forced to use older, less effective, more bee-lethal insecticides like pyrethroids. Now environmentalists want a similar ban imposed by the EPA in the United States.

That’s a terrible idea. The fact is, bee populations tend to fluctuate, especially by region, and “it’s normal for a beekeeper to lose part of his hive over the winter months,” notes University of Montana bee scientist Dr. Jerry Bromenshenk. Of course, beekeepers want to minimize such losses, to avoid having to replace too many bees or hives before the next pollination season begins. It’s also true that the United States did experience a 31% loss in managed bee colonies during the 2012-2013 winter season, according to the US Agriculture Department.

Major losses in beehives year after year make it hard for beekeepers to turn a profit, and many have left the industry. “We can replace the bees, but we can’t replace beekeepers with 40 years of experience,” says Tim Tucker, vice president of the American Beekeeping Federation. But all these are different issues from whether bees are dying off in unprecedented numbers, and what is causing the losses.

Moreover, even 30% losses do not mean bees are on the verge of extinction. In fact, “the number of managed honeybee colonies in the United States has remained stable over the past 15 years, at about 1.5 million” – with 20,000 to 30,000 bees per hive – says Bryan Walsh, author of the Time article.

That’s far fewer than the 5.8 million managed US hives in 1946. But this largely reflects competition from cheap imported honey from China and South America and “the general rural depopulation of the US over the past half-century,” Walsh notes. Extensive truck transport of managed hives, across many states and regions, to increasingly larger orchards and farms, also played a role in reducing managed hive numbers over these decades.

CCD cases began spiking in the USA in 2006, and beekeepers reported losing 30-90% of the bees in many hives. Thankfully, incidents of CCD are declining, and the mysterious phenomenon was apparently not a major factor over the past winter. But researchers are anxious to figure out what has been going on.

Both Australia and Canada rely heavily on neonicotinoid pesticides. However, Australia’s honeybees are doing so well that farmers are exporting queen bees to start new colonies around the world; Canadian hives are also thriving. Those facts suggest that these chemicals are not a likely cause. Bees are also booming in Africa, Asia and South America.

However, there definitely are areas where mass mortalities have been or remain a problem. Scientists and beekeepers are trying hard to figure out why that happens, and how future die-offs can be prevented.

Walsh’s article suggests several probable culprits. Topping his list is the parasitic Varroa destructor mite that has ravaged U.S. bee colonies for three decades. Another is American foulbrood bacteria that kill developing bees. Other suspects include small hive beetles, viral diseases, fungal infections, overuse of miticides, failure of beekeepers to stay on top of colony health, or even the stress of colonies constantly being moved from state to state. Yet another might be the fact that millions of acres are planted in monocultures – like corn, with 40% of the crop used for ethanol, and soybeans, with 12% used for biodiesel – creating what Walsh calls “deserts” that are devoid of pollen and nectar for bees.

A final suspect is the parasitic phorid fly, which lays eggs in bee abdomens. As larvae grow inside the bees, literally eating them alive, they affect the bees’ ability to function and cause them to walk around in circles, disoriented and with no apparent sense of direction. Biology professor John Hafernik’s San Francisco University research team said the “zombie-like” bees leave their hives at night, fly blindly toward light sources, and eventually die. The fly larvae then emerge from the dead bees.

The team found evidence of the parasitic fly in 77% of the hives they sampled in the San Francisco Bay area, and in some South Dakota and Central Valley, California, hives. In addition, many of the bees, phorid flies and larvae contained genetic traces from another parasite, as well as a virus that causes deformed wings. All these observations have been linked to colony collapse disorder.

But because this evidence doesn’t fit their anti-insecticide fund-raising appeals, radical environmentalists have largely ignored it. They have likewise ignored strong evidence that innovative neonicotinoid pest control products do not harm bees when they are used properly. Sadly, activist noise has deflected public and regulator attention away from Varroa mites, phorid flies, and other serious global threats to bees.

The good news is that the decline in CCD occurrence has some researchers thinking it’s a cyclical malady that is entering a downswing – or that colonies are developing resistance. The bottom line is that worldwide trends show bees are flourishing. “A world without bees” is not likely.

So now, as I said in a previous article on this topic, we need to let science do its job, and not jump to conclusions or short-circuit the process. We need answers, not scapegoats – or the recurring bee mortality problem is likely to spread, go untreated or even get worse.

_____________

Paul Driessen is senior policy analyst for the Committee For A Constructive Tomorrow (www.CFACT.org) and author of Eco-Imperialism: Green power – Black death.

From http://www.daff.gov.au/animal-plant-health/pests-diseases-weeds/bee/honeybees-FAQs — What effect has Varroa had on the number of managed bee hives in other countries?

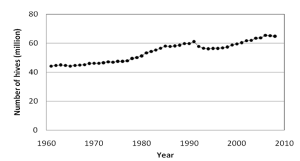

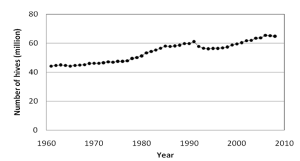

Figure 1. The number of managed honey bee hives in the world from 1961-2008 (FAO Stat, 2011).

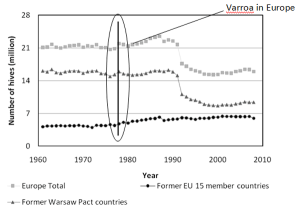

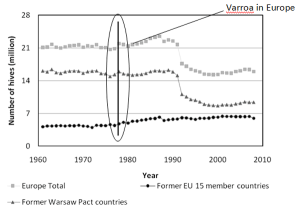

Varroa had no perceptible effect on the number of hives reported in Europe. The number of honey-bee hives in Europe declined sharply in the early 1990s, coinciding with the end of communism, and the end of state support for beekeepers, in the previously communist bloc countries of Eastern Europe. The number of hives reported Western European countries remained unchanged over the same period of time.

Figure 2. The number of managed hives in the whole of Europe, former Warsaw Pact countries and former EU 15 member countries from 1961-2008 (Food and Agricultural Organization Stat, 2011).

Figure 2. The number of managed hives in the whole of Europe, former Warsaw Pact countries and former EU 15 member countries from 1961-2008 (Food and Agricultural Organization Stat, 2011).

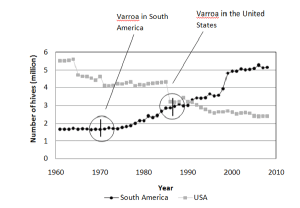

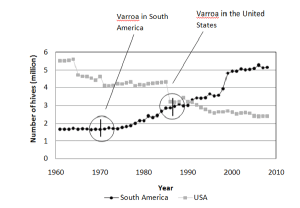

In the United States the number of managed hives declined steadily since the late 1940s, around 40 years before Varroa became established there. This decline reflects declining terms of trade for United States beekeepers as the result of competition with lower-cost honey-producing countries in South America. In contrast, due to their competitive advantage, the number of hives in South America has grown steadily since the mid-1970s, despite Varroa already being established there. However, the J strain of V. destructor in South America is less damaging than the K strain of V. destructor in the United States.

Figure 3. The number of managed honey bee hives in the Unites States and South American countries from 1961-2008 (FAO Stat, 2011).