Gennady Stolyarov II Speaks with Steele Archer of Debt Nation on Transhumanism and Emerging Technologies

Gennady Stolyarov II

Gennady Stolyarov II

Steele Archer

Gennady Stolyarov II

Gennady Stolyarov II

Steele Archer

Schools of thought are frequently named after their country or place of origin. The Chicago School, the Frankfurt School, and the Scottish Enlightenment are just some of the many examples. The geographical place is a simple shorthand for something that would otherwise be difficult to specify and name. That is also the case for the Austrian School of Economics. Or at least that is what we commonly believe. Austrian is nothing more than a shorthand for a school of economics that focuses on market process rather than outcomes, emphasizes the subjective aspects of economic behavior, and is critical of attempts to plan or regulate economic processes. Sure it originated in Austria, but it is largely neglected there today, and currently the school lives on in some notable economics departments, research centers, and think tanks in the United States. The whole ‘Austrian’ label is thus largely a misnomer, a birthplace, but nothing else.

But what if Austrian, or more specifically Viennese, culture is essential to understanding what makes this school of thought different? What if the coffeehouse culture of the Viennese circles, the decline of the Habsburg Empire, the failure of Austrian liberalism, the rise of socialism and fascism, and the ironic distance at which the Viennese observed the world, are all essential to understanding what the school was about? It would be exciting to discover that the Vienna of Gustav Mahler, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Sigmund Freud, Gustav Klimt, and Adolf Loos, would also be the Vienna of Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises, and Friedrich Hayek. And if that is so, how would that change how we think about this school and about the importance of cultural contexts for schools of thoughts more generally?

That is the subject of my recent book The Viennese Students of Civilization (Cambridge University Press, 2016). It demonstrates that the literature, art, and cultural atmosphere are all essential ingredients of Austrian economics. The Viennese circles, of which the most famous was the Vienna Circle or Wiener Kreis, are the place where this type of economics was practiced and in which it came to maturity in the interwar period.

The hands-off attitude first practiced at the Viennese Medical School, where it was called therapeutic skepticism, spread among intellectuals. They dissected a culture which was coming to an end, without seemingly worrying too much about it. As one commentator wrote about this attitude “nowhere is found more resignation and nowhere less self-pity.”¹ One American proponent of the Viennese medical approach even called it the ‘laissez-faire’ approach to medicine.² The therapeutic skepticism, or nihilism as the critics called it, bears strong resemblance to the Austrian school’s skepticism of the economic cures propounded by the government. Some of the Austrian economists, for instance, have the same ironic distance, in which the coming of socialism is lamented, but at the same time considered inevitable. That sentiment is strongest in Joseph Schumpeter. But one can also find it in Ludwig von Mises, especially in his more pessimistic writings. In 1920, for example, he writes: “It may be that despite everything we cannot escape socialism, yet whoever considers it an evil must not wish it onward for that reason.”³

That same resignation, however, is put to the test in the 1930’s when Red Vienna, the nickname the city was given when it was governed by the Austro-Marxists, becomes Black Vienna, the nickname it was given under fascism. The rise of fascism posed an even greater threat to the values of the liberal bourgeois, and at the same time it demonstrated that socialism might not be inevitable after all. One of my book’s major themes is the transformation from the resigned, and at times fatalistic, study of the transformation of the older generation, to the more activist and combatant attitude of the younger generation. Friedrich Hayek, Karl Popper, Peter Drucker as well as important intellectual currents in Vienna start to oppose, and defend the Habsburg civilization from its enemies. That is one of the messages of Freud’s Civilization and its Discontents, of Hermann Broch’s novel The Death of Virgil, of Malinowski’s Civilization and Freedom, of Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, Drucker’s The End of Economic Man, and of course Popper’s The Open Society and its Enemies. It is also the message of the most famous book of the period on civilization The Civilizing Process by the German sociologist Norbert Elias. These intellectuals fight the fatalism and the acceptance of decline, and instead start to act as custodians or defenders of civilization.

In the process the relationship between natural instincts, rational thought, and civilization undergoes a major transformation. Civilization — our moral habits, customs, traditions, and ways of living together — is no longer believed to be a natural process or a product of our modern rational society. Rather, it is a cultural achievement in need of cultivation and at times protection. Civilization is a shared good, a commons, which can only be sustained in a liberal culture, and even there individuals will feel the ‘strain of civilization’ as Popper put it. That is the strain of being challenged, of encountering those of different cultures, and of carrying the responsibility for our own actions. Hayek adds the strain of accepting traditions and customs which we do not fully understand (including the traditions and customs of the market). Similar arguments are made by Freud and Elias.

If that is their central concern then the importance and meaning of their contributions is much broader than economics in any narrow sense. That concern is the study, cultivation and, when necessary, protection of their civilization.

To some this might diminish the contributions of the Austrian school of economics for they might feel that they were responding to a particular Viennese experience. The respected historian Tony Judt for example has claimed that: “the Austrian experience has been elevated to the status of economic theory [and has] come to inform not just the Chicago school of economics but all significant public conversation over policy choices in the contemporary United States.”⁴ He maximizes the distance between us and them, saying that they were immigrants and foreigners with a different experience than ours. But that response only makes sense if the alternative is some disembodied truth, outside of historical experience.

My book, to the contrary, argues that what is valuable, interesting, and of lasting value in the Austrian school is precisely its involved, engaged approach in which economics is one way of reflecting on the times. And those times might be more similar to ours than you might think, as the great sociologist Peter Berger has argued. Troubled by mass migration, Vienna experienced populist politics. The emancipation of new groups lead to new political movements which challenged the existing rational way of doing politics. A notion of liberal progress which had seemed so natural during the nineteenth century could no longer be taken for granted in fin-de-siècle and interwar Vienna. That foreign experience, might not be so foreign after all.

For more information on my book, The Viennese Students of Civilization: The Meaning and Context of Austrian Economics Reconsidered, click here.

Erwin Dekker is a postdoctoral fellow for the F. A. Hayek Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics. He is assistant professor in cultural economics at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

1. Edward Crankshaw. (1938). Vienna: The Image of a Culture in Decline, p. 48.

2. Maurice D. Clarke. (1888). “Therapeutic Nihilism.” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 119 (9), p. 199.

3. Ludwig von Mises. (1920). Nation, State, and Economy. p. 217.

4. Tony Judt. (2010). Ill Fares The Land. p. 97–98.

Earlier this year, a number of Uber cars in Poland came under attack by a group of vandals who were likely taxi drivers. In general, these types of vandalism have a long tradition in human history and have contributed to keeping populations’ general living standards at very low levels.

Attacks on Uber drivers are simply the latest chapter in a long story of efforts to intimidate and destroy innovators who are moving markets and societies in new and unfamiliar directions.

Reactions to Early Machines

For a very long time, separation of grain from the chaff was done in a very primitive manner. The process took weeks, involved hard working men, hard working women feeding them, and also children working as additional helpers. Finally, someone invented a threshing machine that allowed farmers to get rid of all this hard work: the machine could do the job much faster with less physical labor involved.

The change happened contrary to what many historical books claim: the move to threshing machines did not occur because of the patent system put in place 150 years before the change. It happened because social and political forces were too weak to stop it from happening.

Beginning in the eighteenth century in Europe, the entrepreneurial class was growing. They were a group of small profit-driven innovators interested in selling various products, and beating their competitors to markets. This “Great Change” was driven forward by many cultural, religious, political, legal, and technological factors.

At first, threshing machines were very imperfect. They didn’t always work well, and they also were expensive. There was a lot of room for improvements, and for making them better, faster, and cheaper. As they were slowly improved, it quickly became apparent the new machines were more efficient than the old manual methods. It was only a matter of time until someone would realize that steam engines could be combined with the threshing machines.

Not surprisingly, threshing machines were not welcomed by everyone. Swing Riots flared up and the Luddite movement attempted to crush technological innovation. Despite such obstacles, the entrepreneurs won out, paving the way for the future chain of market innovations, well symbolized by the modern farmer sitting in the modern air-conditioned tractor (with a good stereo system). Over the past two hundred years, agricultural workers were reduced from more than 80 percent of workers to less than 5 percent.

Economic Growth and Social Change

One of the big mysteries of human history is the question of why rapid technological and innovative growth started only around the nineteenth century. Many new ideas and technological changes were present for ages (and invented centuries before). Other cultures introduced many new innovative ideas as well.

Some steam engines were even being used in ancient times. They were applied in narrow places, however, due to social and political circumstances.

One early example of political resistance is related to us through the Roman Emperor Vespasian’s opposition to new labor saving innovations. Faced with the prospect of replacing workers with machines, Vespasian reputedly said: “You must let me feed my poor commons.”

Vespasian’s reaction is understandable; it is hard to predict what will happen in response to innovations that make certain job skills obsolete. And it’s not just the workers who fear the change. The ruling class, faced with an idle and unemployed population might also fear social upheaval.

The words of Peter Green summarize many of these concerns:

The ruling class were scared, as the Puritans said, of Satan finding work for idle hands to do. One of the great things about not developing the source of energy that did not depend on muscle power was the fear of what the muscles might get up to if they weren’t kept fully employed. The sort of inventions that were taken up and used practically were the things that needed muscle power to start with, including the Archimedean screw. On the other hand, consider that marvelous box gear of Hero’s: it was never used. That would have been a real conversion of power. What got paid for? The Lagids tended to patronize toys, fraudulent temple tricks in large quantities, and military experiments.

Naturally, human history is complicated and subject to many different factors. Nevertheless, there appears to be some truth in the argument that fixed social and political structure did not favor society open to the widespread adoption of innovation. Otherwise, it is hard to explain why so many new technical discoveries were not applied for so long, even though science and intelligence supplied them centuries before. We had to wait for the new political and social arrangements that either were tolerant of new innovations, or were unable to stop them.

Uber and Beyond

Everywhere we look, we see both the creative and destructive power of innovation. First threshing machine sellers lead to reductions in agricultural employment. Later, tractors killed the threshing machines. Telegraph and railway killed communication systems that relied on horses. Cars destroyed the horse industry. Mass production of textiles destroyed the demand for hand-crafted items. Big stores destroyed smaller shops, now discount shops (in parts of Europe) are destroying big stores. Video rentals hampered the cinema industry, now Netflix and others killed video rentals, while Napster’s success (despite its illegality) predicted a coming end to the old music industry. China’s growth and cheap efficient outsourcing reshaped traditional industries in developed countries. (From an economic perspective there is no difference between hiring cheaper labor or hiring a better machine.)

Dell smashed the traditional computer industry with eliminating many middle men. Ikea did something similar in the furniture industry. The internet destroyed regular newspapers, while Google smashed the marketing industry. Amazon destroys bookstores around the world, while Uber is doing the same with the taxi industry.

Economic progress decreases employments in one place, allows for creation of new ones, even in the service sector. During the process of liquidating employment positions, huge economic development is capable of multiplying per capita production within one generation, positively affecting all social classes.

The current state of affairs is not the end of history. Those companies, innovative today, will be endangered tomorrow. Even Jeff Bezos, creator of Amazon.com, admits Amazon won’t last forever:

Companies have short life spans. … And Amazon will be disrupted one day. I don’t worry about it ’cause I know it’s inevitable. Companies come and go. And the companies that are, you know, the shiniest and most important of any era, you wait a few decades and they’re gone.

Mateusz Machaj, PhD in economics; is a founder of the Polish Ludwig von Mises Institute. He has been a summer fellow at the Ludwig von Mises Institute. He is assistant professor at the Institute of Economic Sciences at the University of Wroclaw.

This article was published on Mises.org and may be freely distributed, subject to a Creative Commons Attribution United States License, which requires that credit be given to the author.

On Tuesday, it was announced that over seventeen million new vehicles were sold in 2015, the highest it’s ever been in United States history.

While the media claims that this record has been reached because of drastic improvements to the US economy, they are once again failing to account for the central factor: credit expansion.

When interest rates are kept artificially low, individuals are misled into spending more than they otherwise would. In hindsight, they discover that their judgment errors wreaked havoc on their financial well-being.

This is a lesson that the country should have learned from the Subprime Crisis of 2008. Excessive credit creation led too many individuals to buy homes, build homes, and invest in the housing industry. This surge in artificial demand temporarily spiked prices, resulting in over four million foreclosed homes and the killing of over nine million US jobs.

Instead of learning from the mistakes that sent shock waves throughout most of the planet, the Federal Reserve has continued with its expansionist policies. Since 2009, the money supply has increased by four trillion, while the federal funds rate has remained at or near zero percent. Consequently, the housing bubble has been replaced with several other bubbles, including one in the automotive industry.

Automotive companies have taken advantage of the cheap borrowing costs, increasing vehicle production by over 100 percent since 2009:

Source: OICA

Source: OICA

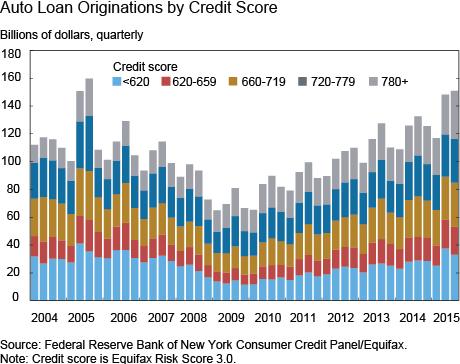

In order to generate more vehicle purchases, these companies have incentivized consumers with hot, hard-to-resist offers, similar to the infamous “liar loans” and “no-money down” loans of the 2008 recession. Dealerships have increased spending on sales incentives by 14 percent since last year alone, and the banners in their shops now proudly proclaim their acceptance of any and all loan applications — “No Credit. Bad Credit. All Credit. 100 Percent Approval.” As a result, auto loans have increased by nearly $80 billion since 2009, many of which have been given to individuals with far-from-stellar credit scores. Today, almost 20 percent of all auto loans are given to individuals with credit scores below 620:

Source: New York Fed

Source: New York Fed

Not only are more auto loans being originated, but they are also increasing in duration. The average loan term is now sixty-seven months (that’s 5.58 years) for new cars and sixty-two (that’s 5.16 years) months for used cars. Both are record numbers.

Average transaction prices for new and used cars are also at their record highs. Used car prices have increased by nearly 25 percent since 2009, while new car prices have increased by over 15 percent. Part of this has to do with the increasing demand for cars generated by the upsurge in auto loans. The main reason, however, is that consumers — taking advantage of the accessibility of cheap credit — are purchasing more expensive body styles. This follows the housing bubble trend, when the median size of a newly built single-family home rose to 2,272 square feet at the start of 2007.

We all know the end result of the Great Recession — prices soared, millions of houses were foreclosed, and unemployment surged. Demand for homes then plummeted, and home prices ultimately dropped by 20 percent each month.

The auto bubble has yet to burst, but its negative effects are already starting to gradually appear. For one, delinquencies on car loans have increased by nearly 120 percent, from just over 1 percent in 2010 to 2.62 percent in 2014. Since cars rapidly depreciate in value, this number is projected to spike. By the time these six, seven, and eight year no-money down loans are due to be paid in full, many of these vehicles won’t be worth paying off anymore — maintenance and loan costs will start exceeding the value of the cars.

According to the Center for Responsible Lending, one in every six title-loan borrowers is already facing repossession fees. If defaults sharply increase in the coming years as projected, the market will become flooded with used cars, and their prices will, with near certainty, fall to a significant degree.

At a time when labor force participation is at its lowest level since 1977 — at a time when real wages are rising less than they have since at least the 1980s — it is imperative that the Federal Reserve stop misleading individuals into making irrational investments. The economy is simply too frail to continue weathering these endless business cycles. Economists, politicians, and the general populace need to start learning from their economic history so they can begin recognizing that favoring debt over thrift isn’t beneficial to the country’s financial well-being. Failure to do so will simply lead to more bubbles, more malinvestment, and more economic headaches in the years to come.

Tommy Behnke is an economics major and Mises University alumnus.

This article was published on Mises.org and may be freely distributed, subject to a Creative Commons Attribution United States License, which requires that credit be given to the author.

Do you know what you don’t know?

Nothing gets me going more than overt economic ignorance.

I know I’m not alone. Consider the justified roasting that Bernie Sanders got on social media for wondering why student loans come with interest rates of 6 or 8 or 10 percent while a mortgage can be taken out for only 3 percent. (The answer, of course, is that a mortgage has collateral in the form of a house, so it is a lower-risk loan to the lender than a student loan, which has no collateral and therefore requires a higher interest rate to cover the higher risk.)

When it comes to economic ignorance, libertarians are quick to repeat Murray Rothbard’s famous observation on the subject:

It is no crime to be ignorant of economics, which is, after all, a specialized discipline and one that most people consider to be a “dismal science.” But it is totally irresponsible to have a loud and vociferous opinion on economic subjects while remaining in this state of ignorance.

Economic ignorance comes in different forms, and some types of economic ignorance are less excusable than others. But the most important implication of Rothbard’s point is that the worst sort of economic ignorance is ignorance about your economic ignorance. There are varying degrees of blameworthiness for not knowing certain things about economics, but what is always unacceptable is not to recognize that you may not know enough to be speaking with authority, nor to understand the limits of economic knowledge.

Let’s explore three different types of economic ignorance before we return to the pervasive problem of not knowing what you don’t know.

1. What Isn’t Debated

Let’s start with the least excusable type of economic ignorance: not knowing agreed-upon theories or results in economics. There may not be a lot of these, but there are more than nonspecialists sometimes believe. Bernie Sanders’s inability to understand why uncollateralized loans have higher interest rates would fall into this category, as this is an agreed-upon claim in financial economics. Donald Trump’s bashing of free trade (and Sanders’s, too) would be another example, as the idea that free trade benefits the trading countries on the whole and over time is another strongly agreed-upon result in economics.

Trump and Sanders, and plenty of others, who make claims about economics, but who remain ignorant of basic teachings such as these, should be seen as highly blameworthy for that ignorance. But the deeper failing of many who make such errors is that they are ignorant of their ignorance. Often, they don’t even know that there are agreed-upon results in economics of which they are unaware.

2. Interpreting the Data

A second type of economic ignorance that is, in my view, less blameworthy is ignorance of economic data. As Rothbard observed, economics is a specialized discipline, and nonspecialists can’t be expected to know all the relevant theories and facts. There are a lot of economic data out there to be searched through, and often those data require careful statistical interpretation to be easily applied to questions of public policy. Economic data sources also require theoretical interpretation. Data do not speak for themselves — they must be integrated into a story of cause and effect through the framework of economic theory.

That said, in the world of the Internet, a lot of basic economic data are available and not that hard to find. The problem is that many people believe that certain empirical facts are true and don’t see the need to verify them by actually checking the data. For example, Bernie Sanders recently claimed that Americans are routinely working 50- and 60-hour workweeks. No doubt some Americans are, but the long-term direction of the average workweek is down, with the current average being about 34 hours per week. Longer lives and fewer working years between school and retirement have also meant a reduction in lifetime working hours and an increase in leisure time for the average American. These data are easily available at a variety of websites.

The problem of statistical interpretation can be seen with data on economic inequality, where people wrongly take static snapshots of the shares of national income held by the rich and poor to be evidence of the decline of the poor’s standard of living or their ability to move up and out of poverty.

People who wish to opine on such matters can, again, be forgiven for not knowing all the data in a specialized discipline, but if they choose to engage with the topic, they should be aware of their own limitations, including their ability to interpret the data they are discussing.

3. Different Schools of Thought

The third type of economic ignorance, and the least blameworthy, is ignorance of the multiple perspectives within the discipline of economics. There are multiple schools of thought in economics, and many empirical questions and historical facts have a variety of explanations. So a movie like The Big Short that clearly suggests that the financial crisis and Great Recession were caused by a lack of regulation might be persuasive to people who have never heard an alternative explanation that blames the combination of Federal Reserve policy and misguided government intervention in the housing market for the problems. One can make similar points about the Great Depression and the difference between Hayekian and Keynesian explanations of business cycles more generally.

These issues involving schools of thought are excellent examples of Rothbard’s point about the specialized nature of economics and what the nonspecialist can and cannot be expected to know. It is, in fact, unrealistic to expect nonexperts to know all of the arguments by the various schools of thought.

Combining Ignorance and Arrogance

What is missing from all of these types of economic ignorance — and what is often missing from knowledgeable economists themselves — is what we might call “epistemic humility,” or a willingness to admit how little we know. Noneconomists are often unable to recognize how little they know about economics, and economists are often unable to admit how little they know about the economy.

Real economic “expertise” is not just mastery of theories and facts. It is a deeper understanding of the variety of interpretations of those theories and facts and humility in the face of our limits in applying that knowledge in attempting to manage an economy. The smartest economists are the ones who know the limits of economic expertise.

Commentators with opinions on economic matters, whether presidential candidates or Facebook friends, could, at the very least, indicate that they may have biases or blind spots that lead to uses of data or interpretive frameworks with which experts might disagree.

The worst type of economic ignorance is the type of ignorance that is the worst in all fields: being ignorant of your own ignorance.

Steven Horwitz is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Economics at St. Lawrence University and the author of Hayek’s Modern Family: Classical Liberalism and the Evolution of Social Institutions. He is a member of the FEE Faculty Network.

This article was published by The Foundation for Economic Education and may be freely distributed, subject to a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which requires that credit be given to the author.

According to the Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT) the artificial lowering of interest rates by the central bank leads to a misallocation of resources because businesses undertake various capital projects that — prior to the lowering of interest rates —weren’t considered as viable. This misallocation of resources is commonly described as an economic boom.

As a rule, businessmen discover their error once the central bank — which was instrumental in the artificial lowering of interest rates — reverses its stance, which in turn brings to a halt capital expansion and an ensuing economic bust.

From the ABCT one can infer that the artificial lowering of interest rates sets a trap for businessmen by luring them into unsustainable business activities that are only exposed once the central bank tightens its interest-rate stance.

Critics of the ABCT maintain that there is no reason why businessmen should fall prey again and again to an artificial lowering of interest rates.

Businessmen are likely to learn from experience, the critics argue, and not fall into the trap produced by an artificial lowering of interest rates.

Correct expectations will undo or neutralize the whole process of the boom-bust cycle that is set in motion by the artificial lowering of interest rates.

Hence, it is held, the ABCT is not a serious contender in the explanation of modern business cycle phenomena. According to a prominent critic of the ABCT, Gordon Tullock,

One would think that business people might be misled in the first couple of runs of the Rothbard cycle and not anticipate that the low interest rate will later be raised. That they would continue to be unable to figure this out, however, seems unlikely. Normally, Rothbard and other Austrians argue that entrepreneurs are well informed and make correct judgments. At the very least, one would assume that a well-informed businessperson interested in important matters concerned with the business would read Mises and Rothbard and, hence, anticipate the government action.

Even Mises himself had conceded that it is possible that some time in the future businessmen will stop responding to loose monetary policy thereby preventing the setting in motion of the boom-bust cycle. In his reply to Lachmann (Economica, August 1943) Mises wrote,

It may be that businessmen will in the future react to credit expansion in another manner than they did in the past. It may be that they will avoid using for an expansion of their operations the easy money available, because they will keep in mind the inevitable end of the boom. Some signs forebode such a change. But it is too early to make a positive statement.

Do Expectations Matter?

According to the critics then, if businessmen were to anticipate that the artificial lowering of interest rates is likely to be followed some time in the future by a tighter interest-rate stance, their conduct in response to this anticipation will neutralize the occurrence of the boom-bust cycle phenomenon. But is it true that businessmen are likely to act on correct expectations as critics are suggesting?

Furthermore, the key to business cycles is not just businessmen’s conduct but also the conduct of consumers in response to the artificial lowering of interest rates — after all, businessmen adjust their activities in accordance with expected consumer demand. So on this ground one could generalize and suggest that correct expectations by people in an economy should prevent the boom-bust cycle phenomenon. But would it?

For instance, if an individual John, as a result of a loose central bank stance, could lower his interest rate payment on his mortgage why would he refuse to do that even if he knows that a lower interest rate leads to boom-bust cycles?

As an individual the only concern John has is his own well-being. By paying less interest on his existent debt John’s means have now expanded. He can now afford various ends that previously he couldn’t undertake.

As a result of the central bank’s easy stance the demand for John’s goods and services and other mortgage holders has risen. (Again it must be realized that all this couldn’t have taken place without the support from the central bank, which accommodates the lower interest-rate stance.)

Now, the job of a businessman is to cater to consumers’ future requirements. So whenever he observes a lowering in interest rates he knows that this most likely will provide a boost to the demand for various goods and services in the months ahead.

Hence if he wants to make a profit he would have to make the necessary arrangements to meet the future demand.

For instance, if a builder refuses to act on the likely increase in the demand for houses because he believes that this is on account of the loose monetary policy of the central bank and cannot be sustainable, then he will be out of business very quickly.

To be in the building business means that he must be in tune with the demand for housing. Likewise any other businessman in a given field will have to respond to the likely changes in demand in the area of his involvement if he wants to stay in business.

A businessman has only two options — either to be in a particular business or not to be there at all. Once he has decided to be in a given business this means that the businessman is likely to cater for changes in the demand for goods and services in this particular business irrespective of the underlying causes behind changes in demand.

Failing to do so will put him out of business very quickly. Now, regardless of expectations once the central bank tightens its stance most businessmen will “get caught.” A tighter stance will undermine demand for goods and services and this will put pressure on various business activities that sprang up while the interest-rate stance was loose. An economic bust emerges.

We can conclude that correct expectations cannot prevent boom-bust cycles once the central bank has eased its interest-rate stance. The only way to stop the menace of boom-bust cycles is for the central bank to stop the tampering with financial markets. As a rule however, central banks respond to the bust by again loosening their stance and thereby starting the new boom-bust cycle phase.

Frank Shostak is an Associated Scholar of the Mises Institute. His consulting firm, Applied Austrian School Economics, provides in-depth assessments and reports of financial markets and global economies. He received his bachelor’s degree from Hebrew University, master’s degree from Witwatersrand University and PhD from Rands Afrikaanse University, and has taught at the University of Pretoria and the Graduate Business School at Witwatersrand University.

This article was originally published by the Ludwig von Mises Institute. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided full credit is given.

Stocks rose Wednesday following the Federal Reserve’s announcement of the first interest rate increase since 2006. However, stocks fell just two days later. One reason the positive reaction to the Fed’s announcement did not last long is that the Fed seems to lack confidence in the economy and is unsure what policies it should adopt in the future.

At her Wednesday press conference, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen acknowledged continuing “cyclical weakness” in the job market. She also suggested that future rate increases are likely to be as small, or even smaller, than Wednesday’s. However, she also expressed concerns over increasing inflation, which suggests the Fed may be open to bigger rate increases.

Many investors and those who rely on interest from savings for a substantial part of their income cheered the increase. However, others expressed concern that even this small rate increase will weaken the already fragile job market.

These critics echo the claims of many economists and economic historians who blame past economic crises, including the Great Depression, on ill-timed money tightening by the Fed. While the Federal Reserve is responsible for our boom-bust economy, recessions and depressions are not caused by tight monetary policy. Instead, the real cause of economic crisis is the loose money policies that precede the Fed’s tightening.

When the Fed floods the market with artificially created money, it lowers the interest rates, which are the price of money. As the price of money, interest rates send signals to businesses and investors regarding the wisdom of making certain types of investments. When the rates are artificially lowered by the Fed instead of naturally lowered by the market, businesses and investors receive distorted signals. The result is over-investment in certain sectors of the economy, such as housing.

This creates the temporary illusion of prosperity. However, since the boom is rooted in the Fed’s manipulation of the interest rates, eventually the bubble will burst and the economy will slide into recession. While the Federal Reserve may tighten the money supply before an economic downturn, the tightening is simply a futile attempt to control the inflation resulting from the Fed’s earlier increases in the money supply.

After the bubble inevitably bursts, the Federal Reserve will inevitably try to revive the economy via new money creation, which starts the whole boom-bust cycle all over again. The only way to avoid future crashes is for the Fed to stop creating inflation and bubbles.

Some economists and policy makers claim that the way to stop the Federal Reserve from causing economic chaos is not to end the Fed but to force the Fed to adopt a “rules-based” monetary policy. Adopting rules-based monetary policy may seem like an improvement, but, because it still allows a secretive central bank to manipulate the money supply, it will still result in Fed-created booms and busts.

The only way to restore economic stability and avoid a major economic crisis is to end the Fed, or at least allow Americans to use alternative currencies. Fortunately, more Americans than ever are studying Austrian economics and working to change our monetary system.

Thanks to the efforts of this growing anti-Fed movement, Audit the Fed had twice passed the House of Representatives, and the Senate is scheduled to vote on it on January 12. Auditing the Fed, so the American people can finally learn the full truth about the Fed’s operations, is an important first step in restoring a sound monetary policy. Hopefully, the Senate will take that step and pass Audit the Fed in January.

Ron Paul, MD, is a former three-time Republican candidate for U. S. President and Congressman from Texas.

This article is reprinted with permission from the Ron Paul Institute for Peace and Prosperity.

During the press conferences of recent FOMC meetings, millions of well-educated investment professionals have been sitting in front of their screens, chewing their fingernails, listening as if spellbound to what Janet Yellen has to tell them. Will she finally raise the federal funds rate that has been zero bound for over six years?

Obviously, each decision is accompanied by nervousness on the markets. Investors are fixated by a fidgety curiosity ahead of each Fed decision and never fail to meticulously observe Janet Yellen and the FOMC, and engage in monetary ornithology on doves (growth- and employment-oriented FOMC members) and hawks (inflation-oriented FOMC members).

Fed watchers also hope for some enlightening information from Ben Bernanke. According to Reuters, some market participants paid some $250,000 just to join one of several dinners, where the ex-chairman spilled the beans. Apparently, he does not expect the federal funds rate to return to its long-term average of about 4 percent during his lifetime.

In a conversation with Jim Rickards, Bernanke stated that a rate hike would only be possible in an environment in which “the U.S. economy is growing strongly enough to bear the costs of higher rates.” Moreover, a rate increase would have to be clearly communicated and anticipated by the markets — not to protect individual investors from losses, Bernanke assures us, but rather to prevent jeopardizing the stability of the “system as a whole.”

It is axiomatic that zero-interest-rate-policy (ZIRP) cannot be a permanent fixture. Indeed, Janet Yellen has been going on about increasing rates for almost two years now. But, how much more lead time will it require to “prepare” the markets? In both September and October the FOMC chickened out, even though we are not talking about hiking the rate back to “monetary normalcy” in one blow. The decision on the table is whether or not to increase the rate by a trifling quarter point!

The Fed’s quandary can be understood a little better by examining what “monetary normalcy,” or a “normal interest rate,” is supposed to be. Or, even more fundamentally: what is an interest rate?

We “Austrians” understand an interest rate as an expression of market participants’ time preference. The underlying assumption is that people are inclined to consume a certain product sooner rather than later. Hence, if savers restrict their current consumption and provide the resources for investment instead, they do so only on condition that they will be compensated by increased opportunities for consumption in the future. In free markets, the interest rate can be regarded as a measure of the compensation payment, where people are willing to trade present goods for future goods. Such an interest rate is commonly referred to as the “natural interest rate.” Consequently, the FOMC bureaucrats would ideally set as a goal a “normal interest rate” that equals the “natural” one.This, however, remains unlikely.

Six Years of “Unconventional” Monetary Policy

ZIRP was introduced six years ago in response to the financial crisis, and three QE programs have been conducted. This so-called “unconventional monetary policy” is supposed to be abandoned as soon as the economy has gathered pace. Despite the tremendous magnitude of these market interventions, the momentum in the US economy is rather lame. Weak Q1 data, which probably resulted from a weak trade balance due to a 15 percent rise of the US dollar, shocked even the most pessimistic of analysts; the OECD and the IMF have revised down their 2015 growth estimates. A long-lasting, self-sustaining growth is out of the question. This confirms the assumption that ZIRP fuels everything under the sun — see “The Unseen Consequences of Zero-Interest-Rate Policy” — except long-term productive investment.And what about unemployment and inflation that are key elements of the Fed’s mandate? The conventional unemployment rate (U3) has returned to its long-run normal level, so the view prevails that things are developing well. However, those figures conceal a workforce participation rate that has fallen by more than 3 percent since 2008, indicating that some 2.5 million Americans are currently no longer actively looking for a new job. However, should the economic situation improve, they would likely rejoin the labor force. Furthermore, the proportion of those only working part-time due to a lack of full-time positions is much higher now than before the crisis. “True” unemployment currently stands rather at about 7.25 percent.

A Weak Economy and Weak Inflation

With regard to inflation, the Fed’s target is 2 percent, as measured by growth of the PCE-index. This aims to buffer the fiat money system against the threat of price deflation. In a deflationary environment, it is believed, the debt-servicing capacity of market participants (e.g., governments, private enterprises, financial institutions, and private households) would come under intense pressure and likely trigger a chain reaction in which loans collapse and the monetary system implodes.

In many countries, and among them the US, inflation is remarkably low — partly due to transitory effects of lower energy and import prices — while low interest rates have merely weaved their way to asset price inflation so far. But, as price reactions to monetary policy maneuvers may occur with a lag of a few years, we should expect that sooner or later inflation will also spill over to normal markets.

As a response to anything short of massive improvement of economic and employment data, a rate hike is scarcely likely, and inflation in the short-term is also unlikely. Moreover, the current composition of the FOMC — which is extremely dovish — implies inflation-sensitive voices are relatively underrepresented. This gives rise to the suspicion that rate hikes are not very likely at all in the scenario in the short-term.

What Will the Fed Do If There’s Real Economic Trouble?

One is concerned about economic development, which has a shaky foundation and headwinds from other parts of the world; it appears that growth has cooled down substantially in the BRICS countries. Meanwhile, China might be on the brink of a severe recession. (Indeed, China was possibly the most decisive factor to nudge the Fed away from raising rates in September and October.) This implies that world-wide interest rates will remain at very low levels and a significant rate hike in the US would represent a sharp deviation in this environment, bringing with it massive competitive disadvantages.

The markets are noticeably pricing out a significant rate hike. The production structure has long since adapted to ZIRP and “short-term gambling, punting on momentum-driven moves, on levered buybacks” are further lifting the opportunity costs of abandoning it. In order to try to rescue its credibility, the Fed may decide to try some timid, quarter-point increases.

But what will they do if markets really crash? Indeed, they are terrified of the avalanche that they might trigger. If there are any symptoms that portend calamity, the Fed will inevitably return to ZIRP, launch a QE4, or might even introduce negative interest rates. Hence, there does not seem to be a considerable degree of latitude such that a return to conventional monetary policy could seriously be expected.

“The Fed is raising rates!” — This has become a running gag.

Ronald-Peter Stöferle is a Chartered Market Technician (CMT) and a Certified Financial Technician (CFTe). During his studies in business administration and finance at the Vienna University of Economics and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, he worked for Raiffeisen Zentralbank (RZB) in the field of Fixed Income/Credit Investments. In 2006 he began writing reports on gold. His six benchmark reports called “In GOLD we TRUST” drew international coverage on CNBC, Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal, The Economist and the Financial Times. He was awarded “2nd most accurate gold analyst” by Bloomberg in 2011.

This article was originally published by the Ludwig von Mises Institute. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided full credit is given.

The great economist Frédéric Bastiat would have turned 214 today. His contributions to liberty have been many, but while so many advocates of free markets focus on The Law, there is another book that represents his legacy even better: Economic Sophisms. This short work of essays epitomizes perhaps his most important contribution: using taut logic and compelling prose to bring the dry field of economics to hundreds of thousands of laymen. Bastiat did not, generally, clear new ground in the field of economics. He read Adam Smith and Jean-Baptiste Say and found little to add to these giants of economic thought. But Bastiat possessed a keen wit and a clear, pithy writing style. His writings have become immensely popular. One-hundred-and-fifty years after his death, essays like “A Petition” are still circulated as an effective counter to progressive economics. Bastiat makes three central contributions in Economic Sophisms. First, he reminds us that we should care about the consumer, not just the producer. Second, he dismantles the argument that there are no economic laws. Third, and more generally, he is one of the few politicians and writers who thought with his head, not with his heart. Bastiat used logic to clearly lay out the consequences of political actions instead of hiding behind good intentions.

Surplus, Not Scarcity

Economic Sophisms expresses a common theme over and over again: we should craft policies that focus on consumers, not on producers.When Bastiat uses these phrases, it can be easy to misinterpret him. Keynes, writing 100 years after Bastiat, hijacked the terms. But Bastiat wasn’t a Keynesian. When he discusses how consumption is the end goal of the economy, what he means is: having goods (which benefits consumers) is more important than making goods (which benefits producers). Put another way, producers prefer scarcity, because it drives up prices. Consumers prefer surplus for the opposite reason. Producers advocate all sorts of methods for reducing the total quantity of goods (theirs excepted, of course). Producers seek to tax goods from other countries that compete with their own. They outlaw machines that would replace them. Producers even favor policies like burning food to drive up food prices, a policy that caused much starvation when it was enacted in the United States during the Great Depression. Consumers, by contrast, prefer abundance. They are happiest when they have a plethora of goods to choose from at a low price. Bastiat points out that we are all consumers, including the producers. The man who produces railroads also uses his wages to buy goods. One can imagine a world with no producers, a paradise in which man’s every need is fulfilled by nature or a benevolent God. But one cannot imagine a world with no consumption. In such a world, man would not eat or drink, have clothing or buy luxuries. Consumption, and quality of life, is the essential yardstick to measure a society’s economic prosperity.

When we enact producer-backed measures like tariffs, Bastiat argues, we favor producers’ interests over consumers’. We show that we’d rather have scarcity than surplus. Taken to its logical extreme, such a policy is absurd. Would anyone truly argue that total scarcity is preferable to having plenty?

The Principle of No Principles

In Bastiat’s day, it was fashionable to claim that no real principles exist. X may cause Y, but a smaller X needn’t cause a smaller Y; it could cause Z instead, or A. Today, we see the same logic: people who claim, for instance, that a minimum wage hike to $100 would kill jobs but that a hike to $10.10 would somehow create them. In essay after essay, Bastiat destroys this myth. Economics is not a foggy morass where up is sometimes down, left can be right, and there are no absolute truths. Economics is not like nutrition, where a glass of wine can heal while two gallons can kill.In economics, a cause will produce a correlational effect, regardless of how large the cause is. If small X causes small Y, large X causes large Y. A minimum wage hike to $100 will kill many jobs; a minimum wage hike to $10.10 will still kill some. The effect does not vary, only the size of it. Indeed, one of Bastiat’s most common argumentative tools is reductio ad absurdum, or carrying a concept to its logical conclusion. Opponents of mechanization want to force railroads to stop at one city and unload goods, thereby generating work for the porters? Very well, says Bastiat. Why not have them stop at three cities instead? Surely that would generate even more work for the porters. Why not stop at twenty cities? Why not have a railroad composed of nothing but stops that will make work for the porters?

By carrying concepts to their logical conclusion, Bastiat provides a firm antidote to the fuzzy thinking of protectionist advocates.

Think with Your Head

In Bastiat’s time, just as today, it was popular to think with one’s heart. “We must do something!” went the rallying cry; never mind the consequences. Good intentions were enough. Make-work, for instance, has always been a favorite policy of those who think with their hearts. They see men and women unemployed and demand government take action. Often, this action takes the form of impeding human progress: using porters instead of railroads, for instance. The initial consequence, for the porters, is positive: more end up employed. But Bastiat recognizes that such policies, while they may protect the porters, harm the economy as a whole. They raise prices and create scarcity. Bastiat looked at more than just the direct consequence of an action. He examined all the outcomes, using taut chains of logic to demonstrate how each policy would impact those whom he was most focused on — the consumer.

Bastiat’s Legacy

Bastiat did not invent any new economic tools or schools of thought. But the clear logic with which he thought through economic ideas, and the clear and witty prose with which he lambasted those who did not do so, have made him one of the most popular economic figures of all time. Bastiat’s ideas in this text have been borrowed, rehashed, and republished for over 150 years. His insights have been appropriated by dozens of prominent thinkers. Most famously, Henry Hazlitt based Economics in One Lesson largely on the essays in Economic Sophisms. As we make note of his 214th birthday, perhaps we should raise a toast to the man whose ideas — in all their adopted formats — have done so much for the cause of liberty.

Julian Adorney is an economic historian, entrepreneur, and fiction writer.

Matt Palumbo is the author of The Conscience of a Young Conservative and In Defense of Classical Liberalism.

This article was published on Mises.org and may be freely distributed, subject to a Creative Commons Attribution United States License, which requires that credit be given to the author.

But can the debate really be as one-sided as I portray it? Well, look at the results: again and again, people on the opposite side prove to have used bad logic, bad data, the wrong historical analogies, or all of the above. I’m Krugtron the Invincible!

Thus wrote the great Paul Krugman. A man so modest as to proclaim that “I think I can say without false modesty, a huge win; I (and those of like mind) have been right about everything.”

Quite a claim. Indeed, predictions are extraordinarily difficult. Even to an expert in a subject who has dedicated his life to a field of study, predicting the future proves elusive. Daniel Kahneman referenced a study of 284 political and economic “experts” and their predictions and found that “The results were devastating. The experts performed worse than they would have if they had simply assigned equal probabilities to each of three potential outcomes.”

A whole book of such wildly inaccurate predictions by experts was compiled into the very humorous The Experts Speak with such prescient predictions as Dr. Alfred Velpeau’s “The abolishment of pain in surgery is a chimera. It is absurd to go on seeking it” and Arthur Reynolds belief that “This crash [of 1929] is not going to have much effect on business.” Indeed, a foundational block of Austrian economics (that some Austrians unfortunately forgot regarding premature predictions of hyperinflation) is that the sheer number of variables in the world at large makes accurate forecasting extraordinarily difficult.

So it must be a rare man indeed that can be right about everything. And this man, Paul Krugman is not.

Predicting a Bubble He Recommended

Paul Krugman likes to reference the fact that he predicted the housing bubble. Of course, he also sort of recommended it. From a 2002 column of his,

To fight this recession the Fed needs more than a snapback; it needs soaring household spending to offset moribund business investment. And to do that, as Paul McCulley of Pimco put it, Alan Greenspan needs to create a housing bubble to replace the Nasdaq bubble.

In 2009, when this came out, he denied its obvious implication and wrote, “It wasn’t a piece of policy advocacy, it was just economic analysis. What I said was that the only way the Fed could get traction would be if it could inflate a housing bubble. And that’s just what happened.” So that doesn’t count as a recommendation? It certainly sounded like he was agreeing with Paul McCulley on inflating a housing bubble. And he verified that that’s exactly what he meant in a 2006 interview where he said,

As Paul McCulley of PIMCO remarked when the tech boom crashed, Greenspan needed to create a housing bubble to replace the technology bubble. So within limits he may have done the right thing. But by late 2004 he should have seen the danger signs and warned against what was happening; such a warning could have taken the place of rising interest rates. He didn’t, and he left a terrible mess for Ben Bernanke.

The best Krugman can possibly say is that he thought Greenspan went too far with the housing bubble he recommended.

Deflation is Around the Corner

While running victory laps because the United States hasn’t seen massive price inflation, Krugman seems to have forgotten what his prediction actually was. In 2010 he wrote, “And what these measures show is an ongoing process of disinflation that could, in not too long, turn into outright deflation … Japan, here we come.”

Robert Murphy called him on this and noted Krugman’s response,

… Krugman himself … said of his 2010 analysis: “(In that post, I worried about deflation, which hasn’t happened; I’ve written a lot since about why).”

Note the parenthetical aside, and the timing: Krugman in April 2013 is mentioning in parentheses to his reader that oh yes, as of February 2010 he was “worried about deflation, which hasn’t happened.” In other words, Krugman entered this crisis with a model that predicted how prices would move in response to the economic situation, and chose his policies of government stimulus accordingly. He was wrong, and yet maintains the same policy recommendations.

But of course to Krugman, anyone who predicted price inflation can’t explain why that hasn’t happened. Such people are just those “… who take a position and refuse to alter that position no matter how strongly the evidence refutes it.” Krugman is different.

Europe Will Do Better Than the United States

In 2008, Krugman wrote:

… tales of a moribund Europe are greatly exaggerated. … The fact is that Europe’s economy looks a lot better now — both in absolute terms and compared with our economy.”

Later he noted that “Americans will face increasingly strong incentives to start living like Europeans” and that “he has seen the future and it works.” (I should probably note that that is a quote he borrowed from Lincoln Steffens about the Soviet Union.)

Then Greece went bankrupt and the international consensus is unquestionably that the crisis hit Europe harder.

The Euro Will Collapse

Niall Ferguson counted eleven different times between April of 2010 and July 2012 that Krugman wrote about the imminent breakup of the euro. For example, on May 17th, 2012, Krugman wrote,

Apocalypse Fairly Soon. … Suddenly, it has become easy to see how the euro — that grand, flawed experiment in monetary union without political union — could come apart at the seams. We’re not talking about a distant prospect, either. Things could fall apart with stunning speed, in a matter of months, not years. And the costs — both economic and, arguably even more important, political — could be huge.

Most of these predictions are laced with weasel words such as “might,” “probably,” and “could” (more on that shortly). Still, while I’m no fan of the euro, and it might still collapse, as of today, three years later, it has not. If the word “imminent” means anything at all, Krugman was wrong.

The Sequester Will Doom Us All

Paul Krugman at least admitted the sequester was “relatively small potatoes.” But for “relatively small potatoes” he makes a big deal about it, referring to it as “one of the worst policy ideas in our nation’s history.” And it “will probably cost ‘only’ around 700,000 jobs.” (Note the word “probably” again.)

Then later, he decided that these were actually quite large potatoes, stating,

And, somehow, both sides decided that the way to buy time was to create a fiscal doomsday machine that would inflict gratuitous damage on the nation through spending cuts unless a grand bargain was reached. Sure enough, there is no bargain, and the doomsday machine will go off at the end of next week.

The economy has done quite well since then actually. Indeed, how $85.4 billion dollars in “cuts” (from the next year’s budget not the previous year’s spending) could affect anything in a $17 trillion dollar economy is simply beyond me. And of course, it didn’t.

Interest Rates Can’t Go Below Zero

In March of this year, Krugman wrote in regard to some European bonds with negative nominal yields,

We now know that interest rates can, in fact, go negative; those of us who dismissed the possibility by saying that people could simply hold currency were clearly too casual about it.”

But as Robert Murphy points out, “The foundation for the Keynesian case for fiscal stimulus rests on an assumption that interest rates can’t go negative.” Murphy also points out that Krugman should admit he was wrong again because back in 2009, Krugman wrote,

And the reason we’re all turning to fiscal policy is that the standard rule, which is that monetary policy plus automatic stabilizers should do the work of smoothing the business cycle, can’t be applied when we’re hard up against the zero lower bound. [i.e. zero percent interest]

“Inflation Will be Back”

In 1998, Paul Krugman predicted “Inflation will be back.”

Nope.

“The Rate of Technological Change in Computing Slows”

Same article as the last one, “… the number of jobs for IT specialists will decelerate, then actually turn down.”

Aside from a short dip after the 2001 recession, the answer would be nope again.

Weasel Words and “Accurate Predictions”

Let’s take a look at Paul Krugman’s “accurate prediction” of the financial crisis. On March 2nd, 2007, he predicted the following explanation would be given a year from then for the financial crisis he was sort of predicting,

The great market meltdown of 2007 began exactly a year ago, with a 9 percent fall in the Shanghai market, followed by a 416-point slide in the Dow. But as in the previous global financial crisis, which began with the devaluation of Thailand’s currency in the summer of 1997, it took many months before people realized how far the damage would spread.

So the crisis would begin in China? Almost.

He concluded that column by saying, “I’m not saying that things will actually play out this way. But if we’re going to have a crisis, here’s how.”

That’s a good hedge, just like with the euro. He can say he got the financial crisis right (albeit happening in a different way than he expected), but then say he didn’t get the euro wrong because he added “probably” before any prediction about it.

Normally, there would be nothing wrong with these weasel words. Given the nature of predictions, any prediction that is made should have a qualifier in front of it. It’s simply an admission that you aren’t omniscient. But you can’t eat your cake and have it too. Either Krugman was right about the crisis (sort of) and wrong about the euro (and many other things) or neither should count at all.

Or course, this doesn’t refute Krugman’s theories. But then again, Krugman may want to slow down on his victory laps.

Andrew Syrios is a partner in the real estate investment firm Stewardship Properties. He graduated from the University of Oregon with a degree in Business Administration and a Minor in History.

This article was published on Mises.org and may be freely distributed, subject to a Creative Commons Attribution United States License, which requires that credit be given to the author.